I am a fan of Clet Abraham’s street art that is manifest by the alteration of common street signs throughout Florence. But his anarchic acts don’t stop with a few signs. In a town mired in a 500-year-old artistic patrimony, Clet continues to bemuse residents and visitors alike.

During the dark of the night on January 19 last year, Clet and a couple of friends installed Common Man, a life-size black fiberglass statue, without permission, on Ponte alle Grazie. Common Man (Uomo Comune) bears a striking resemblance to the black cut-out figure on Clet’s altered street signs. The bridge-jumping statue, which from a distance looks like it is made of heavy iron, was enjoyed by all (except perhaps the cultural powers-that-be) with photographs going viral on the internet. It was removed seven days later by city officials, taking weeks and a Facebook campaign to get the statue back into Clet’s possession.

Alexandra Korey of arttrav.com asks “Is lack of permission an essential part of Clet’s art? Position and surprise are elements that contribute to the meaning of the works. Common Man walks perpendicular to traffic on the bridge, proud and determined as he takes the first step in his battle against bureaucracy and the daily grind. His removal, Clet admits, is part of the plan but ‘one can always hope that they might see the light and leave it up, at least for a little while longer.'”

Alexandra continues by quoting Clet: “The Common Man statue is intended as a stimulus to take an important and risky step. It represents one of those moments on one’s life in which one needs to make a decision even not knowing its consequences (the void below him is this unknowingness). So Uomo Comune decides to take this step, and invites everyone to do it. The irony lays in being part of this dangerous spectacle from the safe side of the railing. The act is permanently frozen in limbo, being a sculpture that doesn’t move and will never finish stepping out, and so will never know if his choice was the right one or not – the only way for us to know is if we were to try it ourselves.”

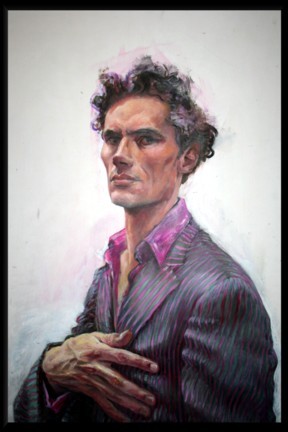

Part of the controversy about displaying modern art in Florence is that foreign artists seem to be given a venue — Gregory Wyatt (U.S.), Botero (Columbia), and more recently Damien Hirst — while resident artists are not afforded the opportunity to show their work. The Palazzo Vecchio raised admission prices for viewing Damien Hirst’s diamond skull. While the Hirst skull was on display, Clet managed to install his self-portrait in a gallery in Palazzo Vecchio, where it went unnoticed for 24 hours. Another act of artistic disobedience.

Clet’s Common Man statue was finally returned to the artist by the officialdom of Florence and in a bit of neighborly cultural nose thumbing, the nearby town of Signa has given the Common Man a permanent home. Instead of walking off a bridge, he is now walking on water. He is striding across the lake in Renai Park.

We look forward to Clet’s next artistic endeavor.