Two weeks ago I wrote about the loss of cheese in the Reggio Emilia region hard hit by a rare 6.0 earthquake. Now a second 5.8 quake has struck nearby, endangering the artisanal production of aceto balsamico tradizionale.

Second Earthquake Devastates Balsamic Vinegar Production

The French AFP news service reported on May 29: The strong quake, which struck Italy on Tuesday (May 22) … has also dealt a blow to Modena’s balsamic vinegar industry — days after a quake in the area hit Parmesan production.

The industry has suffered losses totaling 15 million euros ($18 million), according to the head of the traditional balsamic vinegar consortium Enrico Corsini, who said stocks had been “seriously damaged” as tremors hit the area.

The Pontirol company based in San Felice sul Panaro – one of the worst-hit towns – lost practically everything after its warehouses were flattened, while smaller warehouses owned by other producers were also badly damaged.

The 5.8 quake, which struck Tuesday morning, and the series of tremors of other 5.0 magnitude that followed, “will bring the regional economy to its knees,” Corsini said, adding that 200 businesses in the sector were affected.

The north of the Modena region, where the quake was felt particularly strongly, is home to dozens of balsamic vinegar producers. The consortium said some producers claimed to have lost over 100,000 liters of the costly delicacy. Aceto basalmico tradizionale DOP can cost up to 1,500 euros a liter.

What Is Aceto Balsamico?

To understand the loss, it is important to understand how different aceto balsamico tradizionale is from the balsamic vinegar Americans buy at their local supermarket. Traditional balsamic vinegar is more suited to drizzling on cheese, berries and gelato or gracing the edges of a plate of thin-sliced roast veal, rather than splashed on a salad of leafy greens.

Burton Anderson describes aceto balsamico tradizionale in his book Treasures of the Italian Table as: “The product of an elaborate, prolonged, inspired handiwork or, as some might say, a miracle of man.”

Brette Jackson in La Cucina Italiana also waxes lyrical: “With a lustrous mahogany hue and velvety smooth flavors redolent of plums and cherries (often with a smoky or spicy tang on the finish), traditional balsamic is made in only two places in Italy—the northern Italian provinces of Modena and Reggio nell’Emilia.”

How Is It Made?

In order to bear the name aceto balsamico tradizionale, every aspect of its creation, from grape to bottle, is carefully regulated by Italian DOP (Denominazione di Origine Protetta) standards. This “vinegar” undergoes a lengthy transformation, starting as unfermented juice pressed from indigenous white Trebbiano grapes, which is simmered in large, copper cauldrons for about 24 hours.

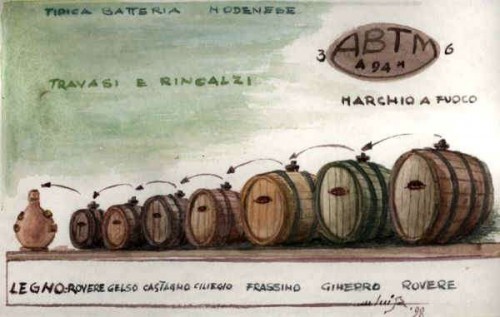

The concentrated syrup, known as mosto cotto, is aged in a series of five barrels of varying sizes and types of wood (some combination of acacia, cherry, oak, chestnut, mulberry, ash, or juniper) known as a batteria. Fitted with large openings that are covered with loosely woven fabric, which allow oxygen to concentrate the must, the five barrels of a batteria range from large to small (the smaller the barrel the greater the concentration and the longer the time “aging”).

The barrels are kept in upper attic spaces, known as an acetaia, because, unlike wine that must have a cool environment, the seasonal fluctuation in temperature only serve to improve the quality of aceto balsamico tradizionale.

It is important to understand that balsamic doesn’t “age” in the same way wine does. Where a single vintage of wine ages in barrels and bottles, a balsamic’s age refers to the length of time the vinegar maker, or acetaio, has worked with a blend; not the age of the contents in a bottle. The rules regarding the labeling continue to change, often causing confusion to the purchaser.

As the aceto balsamico becomes concentrated over time (a minimum of 12 years for the DOP designation), the contents of each barrel must be replenished (topped up) yearly to prevent solidification. This task begins with the smallest and most concentrated barrel in the batteria being filled with younger vinegar from the next largest barrel, and so on, down the line to the largest barrel, which is the youngest and the least concentrated. This barrel is filled with an addition of freshly cooked must.

Each producer is allotted a specific number of bottles of aceto balsamico tradizionale that they can sell, which is indicated by a numbered tag around the bottle’s neck. Bottles from Modena are mandated to be bulb-shaped, while bottles used in Reggio nell’Emilia must be bell-shaped.

The Loss Continues

The first earthquake on May 20, which killed seven people, was followed by nearly a hundred aftershocks. The second large quake on May 22, killed 17 people (mostly those who were told it was safe to go back to work), injured more than 350, and has left 8,000 homeless (in addition to the 6,000 left homeless from the first 6.0 tremor). To discuss the loss of parmesan cheese and balsamic vinegar seems frivolous, in light of the human cost, but this is also a tragedy because it is the livelihood of thousands in the chain that runs from the vineyard and the pastures to the caseifici and acetaie to the stores in Florence, Rome and San Francisco.