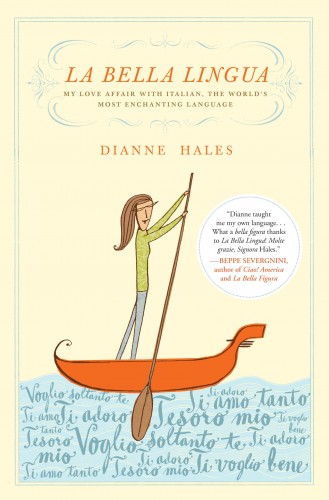

Your day job was as a science and health journalist (I believe, An Invitation to Health is in its 16th Edition), but sometime in the last ten years your writing focus changed to Italy and its language, resulting in the bestselling book La Bella Lingua: My Love Affair with Italian, the World’s Most Enchanting Language. What happened?

Years ago I came to Switzerland to give a talk on sleep (I’d written a book on the subject) and, on an impulse, decided to take a train to Italy. The only Italian I knew was, “Mi dispiace. Non parlo l’italiano.” I was enchanted by everything I saw, but I really wanted to communicate with the Italians who were chattering all around me. So I decided to learn their language.

At the time I had a young child and a busy career, but I began studying Italian any way I could—with books, CDs, audiotapes, classes, tutors. My husband and I began coming to Italy every year on vacation, and we met more and more Italians. I liked them so much that I kept working harder to become fluent so we could become friends—and in many cases, we did.

Along the way, I fell in love with the language. Whenever people ask me why I have such a passion for Italian, I think of Gabriella Ganugi, a chef who heads a prestigious culinary academy in Florence. When she told me that she had originally studied law, I asked how she had acquired her passion for food.

“Signora,” she said. “We do not choose our passions; they choose us.” That’s certainly been my experience. The more Italian I learned, the more I wanted to know about its history—which has everything a writer could want in a subject: drama, passion, comedy, beautiful women, gallant heroes, jealousy, rivalry, unscrupulous scoundrels—not to mention glorious music and fabulous food!

One of my favorite “hidden” places in Florence is L’Accademia della Crusca. What did your research at the Accademia entail and what was your overall impression of the environment of the Medici villa and gardens?

One of the most colorful chapters in Italian’s history revolves around a high-spirited group of Renaissance men in Florence, who dedicated themselves to “separating the wheat from the chaff” of the Italian language. They called their group “L’Accademia della Crusca,” the Academy of the Bran, and went over the top with names and mottos based on the making and baking of bread. They had chairs fashioned from grain barrels and commissioned symbolic paintings on the wooden paddles used to remove loaves from an oven. They adored eating and drinking together at lavish banquets with all sorts of odes and entertainments based on the language.

La Crusca’s original location is now, fittingly enough perhaps, an Irish pub in the heart of Florence, but the Academy’s headquarters are in a Medici villa, where—I’ve been told—Botticelli’s Primavera once hung. I approached it like an awestruck pilgrim. I felt as if I were indeed treading on hallowed ground.

I marveled at the great Sala delle Pale, where the baking shovels—Galileo’s among them—hang like shields on the walls. I also got to touch, very gingerly, a first edition of Il Vocabolario, the first true dictionary in the Western world. The elegant library, a veritable cathedral of Italian literature, filled me with reverence for the language that the “Crusconi” fashioned as painstakingly as any work of art.

The tranquil gardens—well worth a visit—strike me as the perfect complement to La Crusca’s mission. Its founders wanted to select the “most beautiful flowers” in the Italian language—and now we have actual flowers and their verbal equivalents in the same place.

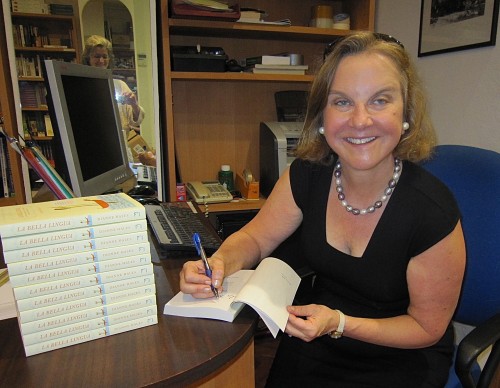

What have been the three most exciting things to happen in your life as a direct result of the publication of La Bella Lingua?

The most incredible was becoming an Italian knight. In recognition of La Bella Lingua’s contributions to the Italian language, President Napolitano named me a Cavaliere dell’Ordine della Stella della Solidarietà Italiana (Knight of the Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity), awarded to foreigners who promote Italian culture. There was a lovely ceremony at the Consulate in San Francisco, where I received some very impressive medals in three sizes—for business, dressy, and formal occasions!

I also have had the opportunity to present La Bella Lingua in Florence, the cradle of the language. I did one reading in the exquisite hall in the Palazzo Tornabuoni where the very first opera was performed and another in the medieval cloister that now houses the Società Dante Alighieri. I felt that I was truly standing in the shadow of Italy’s greatest poets and artists and, more remarkably, speaking a language they would understand if they suddenly came back to life.

The most touching experience has come from readers around the world who follow my blog or join my La Bella Lingua group on Facebook. Some say that my book kindled great pride in their Italian heritage or inspired them to study Italian or travel to Italy. It amazes and delights me that our shared love of Italian has created a real bond that unites us regardless of where we live or what our native tongues are.

My favorite chapter was the one on Italian’s parolacce (bad language). What makes it different from any other language’s swear words? Did you add any to your vocabulary?

In Italy I’ve always heard parolacce (naughty words) swirling around, but I didn’t realize what a rich history they had. I interviewed a scholar of torpiloquio (which, I learned, is the formal term for foul language), who told me that Italians curse differently: Unlike French, German or English speakers, they express powerful emotions like anger, disgust, surprise, and horror with sexual obscenities rather than scatalogical ones. There are literally hundreds of suggestive words, euphemisms and vulgarities for everything related to sex.

In my research, I also came across a Dizionario storico del lessico erotico italiano (Historic Dictionary of the Erotic Italian Lexicon), which lists 3,500 parolacce—a truly impressive number. A friend describes them as verbal spices that add zest to everyday Italian.

But even though Italians swear with gusto and creativity, I don’t advise foreigners to try the same. I never swear in Italy, at least not deliberately. However, I have mispronounced words in ways that sound vulgar—but I’m in good company. Pope Francesco did the same while speaking at the Vatican. I think we should both stick with “Mamma mia!”

What’s your next writing project?

When I was in Florence researching La Bella Lingua, I read newspaper reports about the discovery of archival documents from the family of Lisa Gherardini, the real woman in La Gioconda (the Mona Lisa). Through a family friend, I met the researcher, Giuseppe Pallanti, who gave me a map of the city and marked with X’s the places where Lisa had lived.

When I went to the street where she was born—the rather sad and smelly Via Sguazza—I was struck by the fact that, while everyone knows Mona Lisa’s face (at least as Leonardo portrayed it), no one knows her story.

I began thinking like a journalist and asking the questions of my trade—who, what, where, when, how and why. I rented apartments in Lisa’s neighborhoods in Florence. I came across a 500-year-old history of her family in the state archives. I walked her streets, visited her churches, found the chapel where she should have been buried—and the abandoned convent where she actually was interred. As I immersed myself in every aspect of daily life in Renaissance Florence, Leonardo’s Lisa began to come alive in my imagination.

The culmination of my quest, MONA LISA: A Life Discovered, will be published this August by Simon and Schuster. I’m very excited about the chance to introduce the real Mona Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo—a fiorentina, a daughter of the Renaissance, a teenage bride, a merchant’s wife, a mother of six and, in her husband’s words, a “noble spirit”—to the world. I plan to come to Florence in the fall to celebrate the city’s most famous daughter in her hometown. I’m hoping to meet you and some of the followers of Tuscan Traveler then. A presto!