Over 500 years after her birth we are still talking about her. A genius immortalized her. A French king paid a fortune for her portrait. An emperor coveted her. Every year more than 9 million visitors trek through the Louvre to view her likeness. Yet while everyone recognizes her smile, hardly anyone knows her story or the story of women like her.

Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered, by Dianne Hales is a blend of biography, history, and memoir. It is a book of discovery: about the world’s most recognized face, most revered artist, and most praised and parodied painting; about the woman and the men behind the portrait; and about the author Hales, who undertook a journey of discovery, about herself, her beloved Florence, and a mystery that intrigues her.

Lisa Gherardini (1479-1542) was a quintessential woman of her times, caught in a whirl of political upheavals, family dramas, and public scandals. Her life spanned the most tumultuous chapters in the history of Florence—and of the greatest artistic outpouring the world has ever seen. Her story creates an extraordinary tapestry of Renaissance Florence, with larger-than-legend figures such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Machiavelli.

Who was Mona Lisa, this ordinary woman who rose to such extraordinary fame? Why did the most renowned painter of her time choose her as his model? What became of her? And why does her smile enchant us still?

Dianne Hales agreed to answer a few questions about her book and its subject:

When and how did you come to choose Mona Lisa as the subject for your new book project – Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered?

Years ago while in Florence doing research for La Bella Lingua, I was having dinner at the home of an art historian who casually mentioned that the mother of La Gioconda had grown up in the very same building on Via Ghibellina. I hadn’t known until then that Leonardo’s model was a Florentine woman—Mona (Madame) Lisa Gherardini del Giocondo. I was immediately intrigued by what her life might have been like.

At the time the local papers were reporting discoveries of documents related to Lisa and the Gherardini family. I realized that the archival sleuth, Giuseppe Pallanti, had the same name as a friend of my husband’s. It turned out that they aren’t related, but he arranged a meeting.

When we met—on the roof terrace of the Palazzo Magnani Feroni overlooking Lisa’s childhood neighborhood in the Oltrarno—Pallanti brought a tourist map. With a pencil he marked an “X” for Via Sguazza, where she was born, and another “X” for Via della Stufa, where she lived with her husband and their children.

The very next day I made my way to Via Sguazza, a dank alley that still stinks five centuries after its residents complained about its stench. I was struck by the contrast between the fetid, graffiti-smeared street where Lisa Gherardini was born and the sublime symbol of Western civilization that her portrait has become. The journalist in me sensed a story just waiting to be told. Pretty soon I was off and running.

Describe a bit about the archival research you did. Did you have help? What was the biggest “ah ha” moment and what was the greatest frustration you encountered?

I started at the Florence State Archive, which houses a staggering forty-six miles of manuscripts. With the help of historian Lisa Kaborycha, an American professor who lives in Florence, I tracked down a history of the Gherardini written by a family member in 1586.

I had never done archival research before, and I found it surprisingly exhilarating—deciphering the ornate script, turning the yellowed pages, inhaling their musty scent. I felt that I was traveling through time and encountering flesh-and-blood—Gherardini knights, robber barons, warriors, rebels—all so proud and pugnacious that they coined the word Gherardiname to describe their fierce “Gherardini-ness.”

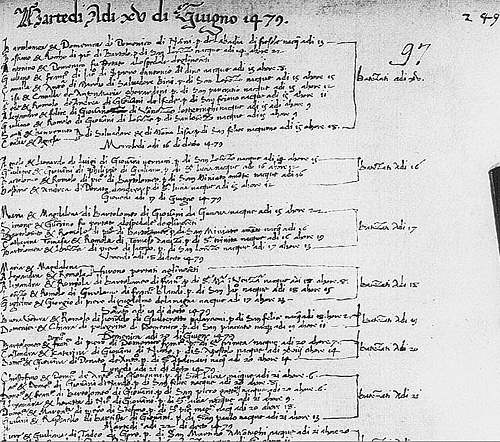

My biggest ah-ha moment came at my computer in California, when I tracked down a record of Lisa’s baptism in the cathedral digital archives. Seeing the hand-scripted words—Lisa & Camilla & Gherardini—in the ledger made her real to me.

The greatest frustration was not finding any words of her own. Leonardo’s Lisa truly is a face without a voice. Fortunately, I found that a relative of hers—Margherita Datini, wife of the famed merchant of Prato—had left behind the largest cache of letters of any woman of her day. This feisty, intelligent, no-nonsense woman, who taught herself to read and write in her twenties, embodied the Gherardini spirit that Lisa may have shared.

Describe the choices you made to tell the story of a woman for whom there is very little “paper trail” and an artist who everybody was talking and writing about.

Thanks to Giuseppe Pallanti’s research, I had a framework for Lisa’s life, including the dates when her children were born and a record of her death. But as I read more about Leonardo and about Florentine history, I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of information. How could I keep Lisa’s story from being lost?

An American art historian gave me some wonderful advice: Inhabit Lisa’s neighborhoods. That’s what I did. I walked the streets where Lisa had lived. I genuflected in the churches where she had worshiped. I explored the locations of the convents where she had placed her daughters.

Ross King, author of Leonardo and the Last Supper, describes my book as “cultural history that reads like a detective novel.” I hadn’t envisioned it quite that way, but I wanted take readers with me on my quest so they could share the step by step revelations of what turned into a true journey of discovery.

How many interviews did you conduct while researching the numerous subjects covered by the book (Leonardo da Vinci, life of Renaissance women, art, politics and commerce in 15th century Florence, and the journey of the painting from Florence to Paris, and much more)?

How many interviews did you conduct while researching the numerous subjects covered by the book (Leonardo da Vinci, life of Renaissance women, art, politics and commerce in 15th century Florence, and the journey of the painting from Florence to Paris, and much more)?

Well over a hundred. I certainly drew on all the skills I had honed in decades as a journalist. Basically I followed the facts wherever they led—to experts in art, history, economics, women’s studies, fashion, food, religion, even antique silk-making. Each of them offered a different perspective. My challenge was to weave the threads together into a tapestry that would bring Mona Lisa and her Florence to life.

One of my friends says she knew she was ready for her oral doctoral exam when she could turn any conversation on any topic to the Italian Renaissance. That’s how I feel about Mona Lisa and Leonardo. Baseball? Did you know that palle (balls) were the symbol of the Medici—and that one of Leonardo’s patrons was Giuliano de’ Medici, who was a political ally of Mona Lisa’s husband?

How much of the project was devoted to research and how much to writing?

They overlapped over a span of more than three years. The feet-on-the-ground research, which I did during extended visits to Florence and Tuscany, kept leading me in new directions. I’d come home and dive back into the library or computer archives.

I didn’t write this book as much as rewrite it—some 80,000 words over and over again. It was the most challenging project I’ve ever undertaken: organizing reams of material, finding the right tone, balancing anecdote and explanation, searching for the most telling details—and then polishing, polishing, polishing. I kept thinking of Leonardo applying tens of thousands of brush strokes to create his portrait of Mona Lisa. He inspired me!

What did you learn about the daily life of women in the late 15th century?

A great deal of research on women has been done in just the last three or four decades–and many of the findings are rather depressing. One historian called Renaissance Florence “among the more unlucky places in Western Europe to be born female.” This was particularly true for poor women, who were typically malnourished and illiterate, bred early, toiled endlessly and died young. Even women of the merchant class, like Mona Lisa, remained second-class citizens who passed from the control of their fathers to their husbands.

This is one reason that I was fascinated to learn that Lisa exercised two of the few prerogatives available to Renaissance women: she decided how to dispose of the property and valuables she inherited from her husband and she chose to be buried, not with him, but in a community of sisters at the convent where her daughter lived.

Italian scholars gave me a more positive perspective than American feminist historians. As one Italiana put it, Renaissance women were not liberated in the way we use the term, but they were strong and central to the most important social institution in Italy: the family. And some, like Lisa Gherardini, inspired great masterpieces of Western art, which may be the most lasting of legacies.

Why do you think Leonardo da Vinci accepted the commission to paint a “housewife” and then carried the portrait around for years?

I believe that something about Lisa herself captivated Leonardo —“something inherent in his vision,” as the art critic Sir Kenneth Clark observed. How else, he asked, could one explain the fact that “while he was refusing commissions from Popes, Kings, and Princesses he spent his utmost skill … painting the second wife of an obscure Florentine citizen?”

Perhaps with his discerning eye, Leonardo saw more than a fetching young mother caught up in the delights and distractions of small children, with a blustering husband and a big quarrelsome blended family. Perhaps what intrigued him as an artist was a flicker of her indomitable Gherardini-ness.

Leonardo left Florence before completing Lisa’s portrait, and it traveled with him to his final home in France. Most of the art historians I interviewed believe that the aging artist spent years refining the painting with delicate brushwork and almost transparent glazes. It may be that during its long metamorphosis, Mona Lisa took on deeper meaning for Leonardo—as a demonstration of all that he had learned about portraiture and all that he understood about human nature. Would Mona Lisa recognize herself in the Louvre portrait? We will never know.

Leonardo left Florence before completing Lisa’s portrait, and it traveled with him to his final home in France. Most of the art historians I interviewed believe that the aging artist spent years refining the painting with delicate brushwork and almost transparent glazes. It may be that during its long metamorphosis, Mona Lisa took on deeper meaning for Leonardo—as a demonstration of all that he had learned about portraiture and all that he understood about human nature. Would Mona Lisa recognize herself in the Louvre portrait? We will never know.

Why does Lisa Gherardini’s story matter? Is a model’s identity relevant in consideration of a work of art?

Mona Lisa ultimately remains what it is: a masterpiece by an unparalleled genius. Yet learning about Leonardo’s model adds new dimensions to appreciation of the portrait. Once I saw only a silent figure with a wistful smile. Now I behold a daughter of Florence, a Renaissance woman, a merchant’s wife, a loving mother, a devout Christian, a noble spirit. I relate to her, not just as a lovely object, but as a real person.

Beyond adding new perspective on the painting, Lisa’s story opens a window onto life in Florence during the most astounding artistic outpouring in history. Hers was the city that thrills us still, bursting into fullest bloom and redefining the possibilities of man—and of woman.

Do you have events scheduled in the U.S. and Italy where you will be discussing Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered? How can we find out about upcoming events?

Yes, I have a busy schedule ahead, with readings and talks in northern California, Chicago, Philadelphia and the New York City area. You can find the details on the events page of my website.

I will be in Florence from September 25 to October 10 and will announce the details on my website. In addition to readings and presentations, I am developing personalized tours of Mona Lisa’s Florence and some programs for writers and storytellers. If any of your readers might be interested, drop me a line at dianne@becomingitalian.com

Have you selected the subject for your next book?

I am currently finishing a very different project: a college textbook on Personal Stress Management with my daughter Julia, a psychology doctoral candidate. However, I so enjoy “living “ in Italy—if only in my head—that I hope to return to an Italian topic soon.

Get Your Copy of Mona Lisa: A Life Discovered

Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.it, Barnes & Noble, iBooks, and at a bookstore near you (including The Paperback Exchange in Florence, Italy). You can also go to Tuscan Traveler’s Amazon Bookstore (same price as online) to find this and other Italian-interest books.

Order the book from Amazon.com, Amazon.co.uk, Amazon.it, Barnes & Noble, iBooks, and at a bookstore near you (including The Paperback Exchange in Florence, Italy). You can also go to Tuscan Traveler’s Amazon Bookstore (same price as online) to find this and other Italian-interest books.