November 4, 2014 will be the 48th anniversary of the Florence Flood of 1966. The memory is still vivid in the minds of most Florentines; either they experienced the flood and/or its aftermath, or they have been told stories of the disaster by their parents or grandparents.

The question in the minds of many who live in the city split by the Arno River is: Can it happen again?

Timeline of the Flood

3 November 1966

In 1966, heavy rains began falling in Tuscany in September. Soon, the earth of the Casentine Forrest, southeast of Florence, was saturated. The rains increased in October and November. It rained the first three days of November. On the 2nd alone, seventeen inches of rain fell in twenty-four hours on Monte Falterona southeast of Arezzo where the Arno is born. The early snow on the mountain melted and rivers of water flowed north and west toward Florence.

The Levane and La Penna dams in Valdarno, north of Arezzo began to emit more than 2,000 cubic meters (71,000 cubic feet) of water per second toward Florence.

At 2:30 pm, the Civil Engineering Department of Florence reported “an exceptional quantity of water.” Cellars in the Santa Croce and San Frediano areas began to flood. Streets failed to drain as the Arno backed up into the city’s drainage system.

Police received calls for assistance from farms and tiny towns north past Florence. The walls along river in the city still held, but floodwaters poured over roads and bridges, cutting off the little villages and forcing people to the roofs of their homes.

A worker died at the Anconella water treatment plant. In A Tuscan Trilogy, Paul Salsini writes: “At the aqueduct, a workman named Carlo Maggiorelli, fifty-two years old, had arrived at 8 o’clock Thursday night, carrying a thermos of coffee, half a loaf of bread and a pack of cigarettes. In a telephone call to officials in Florence, he reported that “everything’s going under.” But he refused to leave; he was responsible for the plant. Later, his body was recovered in a tunnel choked with mud. He was the first victim of the flood of November 4, 1966.”

By midnight on November 3, the Arno River in Florence had risen twenty feet from its normal level, but it still flowed between the high walls through the city.

4 November 1966

At 4:00 am, engineers, fearing that the Valdarno La Penna dam would burst, discharged a mass of water that eventually reached the outskirts of Florence at a rate of 60 kilometers per hour (37 mph). The wall of water overflowed the Levane dam and rushed toward Florence.

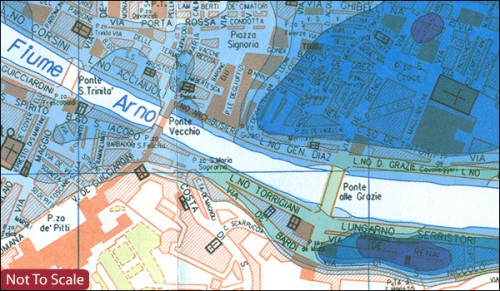

Florence’s newspaper, La Nazione, printed during the night, had a banner headline: “L’Arno Straripa a Firenze” (The Arno overflows at Florence). The article went on to report (translated by Salsini): “The city is in danger of being flooded. At 5:30 this morning water streamed over the embankments, flooding the Via dei Bardi, the Borgo San Jacopo, the Volta dei Tintori and the Corso dei Tintori, the Lungarno delle Grazie and the Lungarno Acciaiuoli. Many families are evacuating their homes. The river banks at Rovezzano and Compiobbi were overtopped shortly after 1 a.m. The Via Villamagna and the aqueduct plant at Anconella were invaded a short time later, and certain areas of the city are in danger of losing their water supply. There are indications that the day ahead may bring drama unparalleled in the history of the city. At 4:30 a.m. military units were ordered to stand by to cope with a possible emergency situation.”

The night guard on the Ponte Vecchio notified the jewelry store owners of the rising tide of water. Prudent vendors who rushed to move their wares were the only shopkeepers in the flooded areas to save their inventories. Later, the stores on the bridge were gutted by the water.

At 7:26am electric power failed in Florence. The Arno flowed over the parapets of San Niccolo bridge, as well as Ponte alle Grazie and the Ponte Vecchio. By 9:00am, hospital emergency generators (the only remaining source of electrical power) failed.

Landslides obstructed roads leading to Florence, while narrow streets within city limits funneled floodwaters, ever increasing in height and velocity.

After breaching its retaining walls on both sides, the Arno flooded the city. On the north side, it swept through the National Library, the Piazza Santa Croce and the church itself. Water filled the Piazza della Signoria, the basement of the Uffizi and the Palazzo Vecchio.

By 9:35 a.m. it reached the Duomo and the Campanile. Ten minutes later, the Piazza del Duomo was flooded. A twenty-foot vortex of water tore three panels from Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gate of Paradise on the east side of the Baptistry and two from Andrea Pisano’s panels on the south.

At the San Lorenzo Mercato Centrale the refrigeration units located below street level were destroyed and the main floor and all of the food stands were awash.

At the Accademia, water inched across the floor toward Michelangelo’s David although the statue was never in real danger.

On the south side, in the Oltrarno, where the land sloped uphill from the river, the damage was less.

The catastrophe was not only caused by the amount of water. The powerful flood ruptured heating oil tanks stored under or at ground level of most of the buildings, and the oil mixed with the water and the tons of muddy topsoil washed down the agricultural Arno Valley, causing far greater damage than that attributed to the water alone.

Twenty thousand families lost their homes, fifteen thousand cars were destroyed, and six thousand shops went out of business. At least thirty people were confirmed fatalities, but some reports put the toll at more than a hundred.

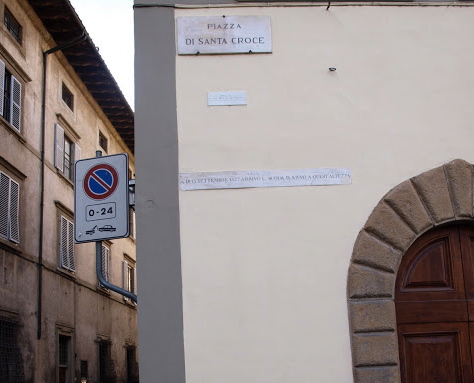

At its highest, the water reached over 6.7 meters (22 ft) in the Santa Croce area, more than twice as high as the flood of 1557.

By 8:00 pm, the water began to recede.

Treasures Damaged or Destroyed

Records after the flood estimated that 1,500 works of art in Florence were disfigured or destroyed. Of these, 850 were seriously damaged, including paintings on wood and on canvas, frescoes and sculptures. Among the casualties were Paolo Uccello’s Creation and Fall at Santa Maria Novella, Sandro Botticelli’s Saint Augustine and Domenico Ghirlandaio’s Saint Jerome at the Church of the Ognissanti, Andrea di Bonaiuto’s The Church Militant and Triumphant at Santa Maria Novella, Donatello’s wooden statue of Mary Magdalene in the Baptistry of the Duomo, Baccio Bandinelli’s white marble Pietà in Santa Croce and Filippo Brunelleschi’s wooden model for the Cupola of the Duomo, in the Duomo’s Museum.

Many considered the greatest loss to be the painted wood Crucifix by Giovanni Cimabue, the Father of Florentine Painting, in the Santa Croce Museum. The water there rose thirteen feet. The heavy wooden crucifix had taken on so much water that it had grown three inches and doubled its weight. The wood cracked and paint chips floated out on the water. After it was removed from the refectory, the cracks widened, mold grew, and the paint continued to flake off. It was years before the cross had shrunk down to its original size. The crevices were later filled in with poplar from the Casentine Forest, where Cimabue obtained the original wood, the same forest where the flood began. The Cimabue Crucifix became the symbol of both the tragedy of the flood and the rebirth of the city after the waters receded.

Archives of the Opera del Duomo (Archivio di Opera del Duomo): 6,000 volumes/documents and 55 illuminated manuscripts were damaged.

National Central Library (Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale Firenze): Located alongside the Arno River, the National Library was cut off from the rest of the city by the flood. The flood damaged 1,300,000 items, including the majority of the works in the Palatine and Magliabechi collections, along with periodicals, newspapers, prints, maps and posters. This was a third of the library’s collections.

Gabinetto Vieusseux Library (Biblioteca del Gabinetto Vieusseux): All 250,000 volumes were damaged, including titles of romantic literature and Risorgimento history; submerged in water, they became swollen and distorted. Pages, separated from their text blocks, were found pressed upon the walls and ceiling of the building.

The State Archives (Archivio di Stato): Roughly 40% of the collection was damaged, including property and financial records; birth, marriage and death records; judicial and administrative documents; and police records, among others.

Can It Happen Again?

Residents of Florence think of the 1966 Flood every year when the winter rains begin – even if they weren’t alive or living in Florence 48 years ago. The Arno still has a shallow riverbed. Each year the water climbs the Ponte Vecchio and covers the rose beds at the nearby Rowing Club, located under the Uffizi Gallery.

The plaques on Florence walls in the historic center remind us of the many floods that happened over the centuries.

The Arno flooded in a catastrophic manner eight times since 1333 – at a rate of about one a century (the one before 1966 was in 1844). Minor floods occur frequently – 13 times in the last 20 years alone.

In the 18th century, engineer Ferdinando Morozzi dal Colle compiled a list of all the floods registered from the year 1177 to 1761. He recorded 54 floods in 600 years: Once every 24 years there was a ‘medium’ flood, every 26 years a ‘big’ flood, and every 100 years an ‘extraordinary’ flood.

Two other disastrous floods, those of 1333 and 1844, both happened on the same day of the year, the day of the 1966 flood: November 4th.

The 1966 flood was the worst of them all.

Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) believed that the Arno could be tamed…but complex bureaucracy prevented any action, and by time the city government approved his plan he had moved on to something else.

“The Arno has been a problem since antiquity,” said Prof. Raffaello Nardi, who headed a special commission responsible for safeguarding the Arno river basin. “And even the old floods were caused as much by human error as by the forces of nature.”

Some believe it is only a matter of time. The Cimabue Crucifix is now hung on a metal device that can be raised far above the level of the 1966 Florence Flood if the waters start to rise again.