Many people do not realize that the majority of frescoes in Florence have been removed and reattached in the place where they were originally painted. The process of “tearing” the fresco off the original wall is called Strappo.

Fresco (affresco) means “wet”. Paint is applied to wet plaster and becomes part of the plaster. This allows the fresco to look virtually the same for over a thousand years, so long as it is not exposed to water or sunlight. Frescoes are permanent because of their chemical composition. Lime paste, which is produced by heating calcium carbonate with limestone, is the active ingredient in the wet plaster on which the fresco is painted. When lime paste is exposed to air it changes back into insoluble calcium carbonate, a hard crust, with the process of carbonatation. If pigment is applied to this type of plaster when wet, it becomes trapped and is permanent because it is chemically stable. (Those who are interested in the full process of creating a 15th century fresco should read “How to paint a fresco (the Renaissance way)” on ArtTrav.com by Alexandra Korey.)

November 3, 2016 will be the 50th anniversary of 1966 flood of the Arno River in Florence, which killed 101 people and damaged or destroyed thousands of art masterpieces and many more rare documents and books. It is congratulations the worst flood in the city’s history since 1557. Many of the historic works have been restored. New methods in conservation were devised and restoration laboratories established. Some of the methods were already known and came into use immediately after the flood. One of those was the strappo technique used to save frescoes immediately after the flood, a race against time.

Frescoes demanded complicated treatment. Normally water, once it evaporates, will leave a layer of residual salt on the surface of the wall that absorbed it. In some instances, the resultant efflorescence obscured painted images. In other cases, the impermeability of the fresco plaster caused the salt to become trapped beneath the surface, causing bubbles to form and erupt, and the paint to fall. The adhesion of the plaster to the wall was often also seriously compromised. A fresco can only be detached when fully dry. To dry a fresco, workers cut narrow tunnels beneath it, in which heaters were placed to draw out moisture from below (instead of outwards, which would have further damaged the paint). Within a few days, the fresco was ready to be detached.

This film of the strappo technique probably dates from the late 50s – early 60s. It documents the phases of removing a 14th century fresco from a niche. The fresco was discovered under a plaster and brick wall. The strappo process is performed by a technician under the direction of the restorer Giuseppe Rossi.

The strappo process begins with a gentle cleaning of the fresco with deionized water and a scalpel to verify the resistance of the color. Next, a layer of cheese cloth is laid over the fresco and is attached or “painted” onto the surface of the fresco with protein colloid glue (animal glue formed through hydrolysis of the collagen from skins, bones, or tendons) that has been dissolved in hot water. After the first layer dries, the process is repeated three or four more times with the same glue and a heavier muslin cloth to create a a strong cover. It is allowed to dry.

The drying glue creates a stronger cohesion with the layer of painted plaster of the fresco than the fresco to the wall behind it. After two or three days the phase of the tear (strappo) begins. A gentle tug on the cloth will start the process of removing the painted plaster layer from the rougher dry plaster wall below with the assistance of a long flexible blade, like a putty knife. The fresco is laid on its face and excess plaster is removed from the back of the fresco layer.

Once the back of the fresco is clean layers of muslin and then canvas are applied using a strong non-water soluble glue (PVA or acrylic resins). This is allowed to dry.

The fresco with its new back is turned over and the layers of cloth and animal glue are removed with hot water and steam. The clothed–backed fresco is then attached to a new support of masonite, polyester resin or fiberglass. The fresco is then restored as needed with watercolor paints. Finally, the fresco is returned to its original position or moved to a safer location.

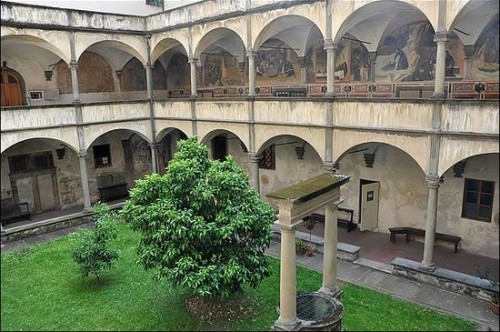

One of the best places in Florence to view frescoes that have been removed from their original plaster wall and replaced is in the cloisters at the Church of Santa Croce.

In the refectory is the 14th century fresco of the Last Supper by Taddeo Gaddi , which has been restored and attached to a new base. The Last Supper was severely damaged during the 1966 flood. Along the side walls of the refectory are fragments of frescoes, some depicting the descent into hell, reposition onto wood backing.

This year in Florence there will be exhibitions, lectures, publications, films and much more celebrating the restoration of Florence after the flood that devastated the city almost fifty years ago.

Other media of interest:

Benoszzo Gozzoli Museum Video of Strappo Technique (Italian language)

PBS NewsHour – “Decades after Florence’s great flood, an art hospital renews still-damaged treasures“

PBS NewsHour – “Photos behind the scenes of the world’s largest art restoration center“