For some reason I’ve been thinking of Machiavelli lately. Near the end of his life he wrote: “I have never said what I believe or believed what I said. If indeed I do sometimes tell the truth, I hide it behind so many lies that it is hard to find.”

It is time to revisit this great political thinker’s words again. The father of modern political science, he lived in the perfect time to analyze the republican government of Florence (he worked 13 years for the republic as a counselor and diplomat), which was followed by the Medici tyrants (they fired him, imprisoned and tortured him and the exiled him forever from Florence). The Prince was his response.

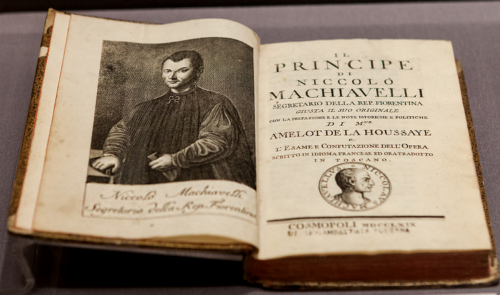

With The Prince, written in 1513, Machiavelli tried to ingratiate himself with the new Florentine prince, Lorenzo di Piero de’ Medici. A bit satirical or hypocritical? After all, for the previous 13 years he had declared that a republic was the ideal form of government, not a city-state governed solely by a dictator, a prince.

Of course, Machiavelli never says anywhere in The Prince that he supports the notion of government by a tyrant. Machiavelli’s book is absolutely practical and not at all idealistic. Leaving aside what government is ideal, The Prince takes for granted the presence of an authoritarian ruler, and tries to imagine how such a ruler might achieve power and hold power. If a country is going to be governed by a dictator, particularly a prince new to the job, one who has never tried to govern, Machiavelli has some advice as to how that prince should rule if he wishes to be successful – to win.

Machiavelli recommends, “one must know how to color one’s actions and be a great liar and deceiver.” He concludes that “… it is a general rule about men, that they are ungrateful, fickle, liars and deceivers, fearful of danger and greedy for gain.” He states that a prince who acts virtuously will soon come to his end in a city-state of people who are not virtuous themselves.

Thus, the successful prince must be dishonest and immoral when it suits him. He states that “…we see from recent experience that those princes have accomplished most who paid little heed to keeping their promises, but who knew how to manipulate the minds of men craftily. In the end, they won out over those who tried to act honestly.”

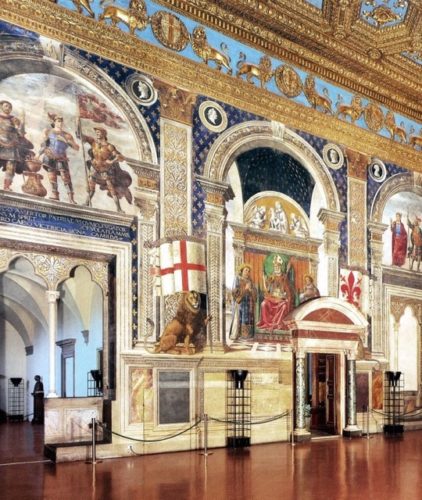

To walk in the footsteps of Machiavelli in Florence, first tour the Palazzo Vecchio where he spent many years in service of the Republic. Find the Old Chancellery, a small room through a door of the Sala dei Gigli.. This was Machiavelli’s office when he was Secretary of the Republic. His polychrome bust in terracotta and a portrait by Santi di Tito are displayed. They both are probably modeled on his death mask. In the center of the room, on the pedestal is the famous Winged Boy with a Dolphin by Verrocchio, brought to this room from the First Courtyard.

In the Uffizi, look for his portrait high on the wall of the first corridor. In the cortile of the Uffizi find a full-sized sculpture of the political philosopher.

Visit the Bargello where Machiavelli also worked and where there is a marble bust of the diplomat by Antonio del Pollaiolo displayed.

Visit the Palazzo Strozzi, the seat of the National Institute of Renaissance Studies, where the Machiavelli-Serristori Foundation conserves ancient volumes of Machiavelli’s extensive writings. The palace of the Strozzi family was a much more welcoming place to Machiavelli due to their hatred of the Medici. Inside there is a painting of Machiavelli by Rosso Fiorentino.

To get the full Machiavelli experience it is necessary to travel to the medieval hamlet of Sant’Andrea in Percussina situated in the Tuscan hills where Machiavelli went to live and work in exile from his beloved Florence. A wonderful NYTimes piece In Tuscany, Following the Rise and Fall of Machiavelli tells of the experience.

Finally, return to the city and walk down Via Guicciardini to #18, in the Oltrarno, to find a plaque on the wall of the last place he lived for a short time (allowed to reenter Florence by the Medici) and where he died in 1527.

Did he really believe the end justifies the means? Go to the Basilica of Santa Croce and contemplate that thought beside his tomb.

“Everyone sees what you appear to be, few experience what you really are,” Machiavelli wrote in The Prince. Again, for some reason I’m thinking about Niccolò Machiavelli today.