Coming of age in 1859, Englishman Frederick Stibbert settled in the villa his mother Giulia bought in Florence at the edge of town in the Montughi neighborhood. He was wealthy due to a large inheritance that he was determined and able to increase by means of financial dealings in Italy and in the rest of Europe. His real passion, however, was art – it was the only thing, reportedly, he had been good at in school – not as an artist, but as a collector.

He began to fill his mother’s villa with items he obtained in his travels as an international financier. For almost fifty years he frequented European art markets. He also traveled to Asia and Africa. The trips lasted for months. He returned every time with hundreds of pieces. Soon he also had dozens of agents across the world sourcing items for his collection.

In 1874, finding that the Villa of Montughi was not able to accommodate his mother and sisters and so many collectibles, Stibbert bought the neighboring Villa Bombicci. Between 1876 and 1880, he joined the two villas into one building. He renovated the spaces for the collections and those for family life. To create display rooms, each with its own theme, Stibbert hired artisans such as Gaetano Bianchi, an expert in neo-modern atmospheres, the stucco artist Michele Piovano, the ceramist Ulisse Cantagalli, and an army of furniture makers, carvers, gunsmiths and outfitters.

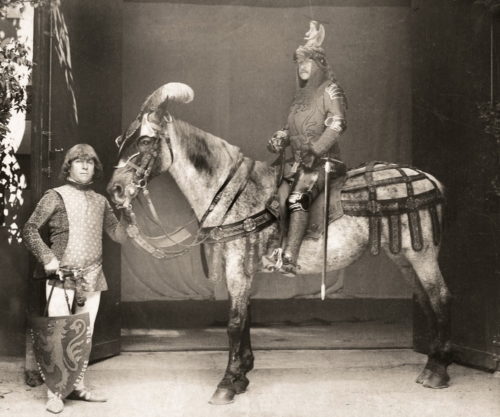

Stibbert was interested in the history of costume and uniforms from the Renaissance to the First Empire, but his obsession was for armor and armaments, not only from the knights of Europe, but also from Asia, especially Japan, and Islamic countries. He had distinctive halls created in the combined villas to house the armory, including the Sala da Cavalcata, a grand hall with a cavalcade of human and equine plaster figures clad in European armor, overlooked by a huge figure of St. George battling a dragon.

Stibbert not only loved to acquire armor, he loved to dress in the armor from his collection, and talked relatives and friends to join in the interpretation of historical scenes. In one historical procession, organized in 1887 for the inauguration of the façade of the Duomo (for which he donated thousands to fund the construction), he paraded as a fourteenth-century knight, with a custom-made armor.

Today, this eccentric museum still exhibits Stibbert’s own ideas of how the collection should be arranged. In other words, the rooms are specially designed to create the right atmosphere, the items are presented in ensembles, some of the costumes are remade and arranged in semi-theatrical poses.

The First Empire collection of all things Napoléon (whom Stibbert’s father fought as a Coldstream Guard) fills an entire room.

The collection includes French arms, such as combat and ceremonial swords, sabers, and dragoon helmets, plateware and jewelry, the a decree for the modification of coats of arms of the city of Florence dated 1811 and signed by Napoleon, and the coronation costume worn by Napoléon in the Duomo in Milan in 1805. The coronation cape is green (in honor of Italy) and covered in Napoléonic symbolism: notably, embroidered palms, laurels and bees, stars surrounded by garlands composed of corn cobs and oak leaves, Napoléonic ‘N‘s, and on the left shoulder an embroidered plaque of the Grand Master of the Royal Order of the Iron Cross, with the inscription ‘Dieu me l’a donné, gare à qui y touche‘ (‘God gave me it. Heaven help him who touches it’). The shoes worn by Napoléon during the ceremony complete this unique costume.

Stibbert wasn’t trained in art history, museum curation, or fine art. Unlike Bereson, Horne and Bardini, he did not purchase works necessarily for their value or for resale. He bought what he liked and he kept it all. The collection at his death in 1906 contained over 50,000 pieces. The result is an extraordinary example of eclecticism, in which different styles and heterogeneous collections coexist, united by the strong personal stamp of the collector.

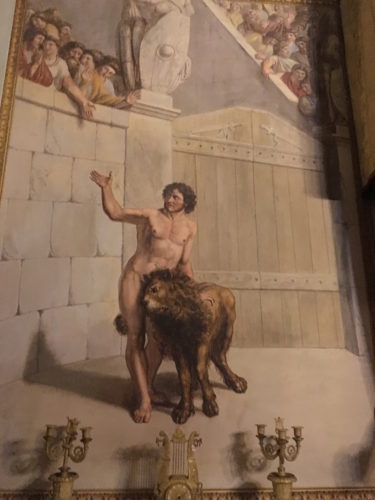

Inside the museum, where you tour with a guide, the rooms follow one another presenting European, Islamic and Japanese weapons and armor, in environments that suggest the atmosphere of distant cultures, followed by neo-baroque or rococo rooms, full of paintings, portraits and wooden sculptures, religious art, including reliquaries, and vestments, furnishings and porcelain, travel souvenirs. The family’s living spaces have now merged seamlessly into the collection.

The vast garden behind the villa is laid out in the English style, with temples, grottoes and fountains, affording a delightful walk on leaving the museum. During a trip to Egypt made after the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, Stibbert bought some artifacts later used in the construction of the small temple that overlooks a small lake. He, along with his mother Giulia and sister Sofronia, were honored with awards for the garden and creation of various new flower varieties.

Today, the museum frequently curates excellent themed exhibits highlighting certain aspects of the Stibbert collection. The museum is open from 10am to 2pm Monday through Wednesday and from 10am to 6pm on Friday through Sunday. The guided visits start on the hour and last for about one hour. Last entrance an hour before closing. Closed Thursday. Tickets are 8 euro. The garden can be visited without a ticket.

Special Exhibit: Feasts and Banquets – The Art of Preparing Banquet Halls

From March 30, 2018 to January 6, 2019, the Stibbert Museum presents “Conviti e Banchetti – L’Arte di Imbandire le Mense” which pulls hundreds of items from the Stibbert collection as well as from other sources such as Ginori ceramics, Meschi artificial flowers, and Opera Laboratori Fiorentini for sugar sculptures. Exhibits and items include those for the Renaissance banquet table, a Baroque feast, 18th and 19th century flatware and table settings, as well as kitchen equipment through the ages.