For Americans, licorice most likely means chewy candies called Red Vines or Twizzlers, which have no actual licorice in the recipe (corn syrup, wheat flour, citric acid, artificial flavor, red 40). (Red Vines also comes in Black Twists (molasses, wheat flour, corn syrup, caramel color, licorice extract, salt, artificial flavor).) Real licorice (liquorice to the Brits) comes from the root of a herbaceous perennial legume native to southern Europe, including Italy and parts of Asia, such as India.

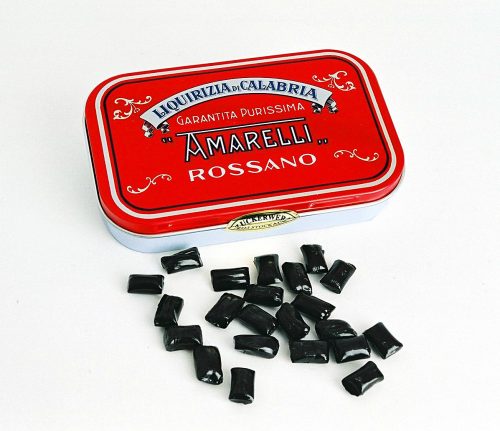

In Italy, licorice is enjoyed as a hard or soft candy, usually button-shaped or tiny squares, with no added sugar because the licorice root has its own sweetness. In fact, the woody root itself was used (and for some, still is) as chew stick or toothbrush, prized for its anti-bacterial and breath-freshening qualities.

The history of licorice in Calabria begins in the 11th century. Old records testify that in the 16th century the Amarelli family and others were interested in the roots of a particular plant that grew wild on their extensive Calabrian estates (then in the Kingdom of Naples). Its name was liquirizia, scientifically called glycyrrhiza glabra, which means “sweet root”.

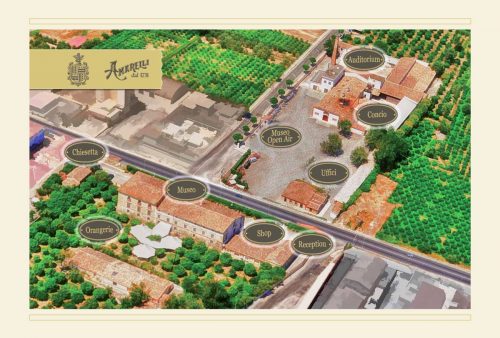

Today, visitors taking a road trip in Calabria are in for a once-in-a-lifetime experience because the Amarelli family, licorice producers since 1731, has opened the Giorgio Amarelli Museo della Liquirizia, in Rossano near Sibari in the region of Calabria. The Licorice Museum was awarded the Premio Gugghenheim Impresa & Cultura (Guggenheim Culture and Business Prize) in 2001 and in 2004 Poste Italiane dedicated a postage stamp to it, part of the series Il Patrimonio Artistico e Culturale Italiano.

The Museum is located in the late 15th century historic residence, which was both home and production plant of the Amarelli family. The family’s history is presented through a series of engravings, documents, books and vintage photographs. The center gallery exhibits the history of licorice and the traditional system of its production, from the root bales, to the manual tools, to the bronze and porcelain molds and the first experimental machines. There are also documents about administrative procedures from the 18th and 19th centuries: manufacturing trade journals, accounting books, payments records and correspondence between manufacturers and government authorities. An old shipping office is reconstructed.

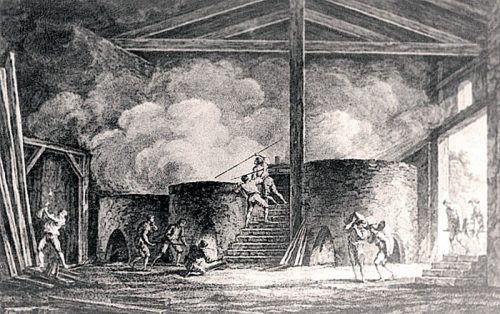

Visitors can also tour the production of Amerielli licorice, which still takes place in the historic eighteenth-century Concio, the original production site, across the road from the museum. In 1731 Amarelli’s established the concio, one of the first pre-industrial factories in the area to extract the juice of the licorice plant roots. The shiny, black licorice produced was not sweetened beyond the sugars naturally found in the root.

Historically, the roots were gathered and stored outside the factory (as they are today). The process began when the roots were milled by a big grindstone, then boiled (no grindstone today, but still boiled). The juice obtained was put through a sieve, cooked in great pots until the mass was reduced and thickened. While still warm and soft, it was hand-worked into licorice sticks and tiny buttons or squares. Find videos of the process here and here.

In 1907, steam boilers were installed. In 1919 the design of the first metal pocket-sized carrying cases for licorice drops was complete. These served to preserve the quality and in the following years became important for marketing with art-decò images still popular today.

In the present day, the process of root selection, juice extraction, boiling and reduction in modern facilities, in compliance with all the current regulations, computerized and automatically controlled, but the final product is controlled by the mastro liquiriziaio.

After three centuries the Amarelli Company, a member of the exclusive Les Hénokiens (an association of companies who have been continuously operating and remain family-owned for 200 years or more, and whose descendants still operate at management level), still produces a very high quality licorice, which can be eaten pure or soft or sugar-coated or tasted as delicious liqueur in candies, brandy and spirits. Amarelli licorice is even used in a Florentine toothpaste.

So give up the sugary fake chews and buy the real Italian licorice. As one reviewer said, “It’s not your father’s licorice, but it IS your grandfather’s licorice. (His grandmother is Calabrian.)