We weren’t there for the celebrations, but in August the town of Predappio, Italy, seemed haunted by Benito Mussolini, all the same.

Most Italians just try to forget about it, but they have just had to face up to this tricky subject again, as October 28 is the 90th anniversary of Mussolini’s “March on Rome” (1922) that brought the Fascist leader to power and enabled him to stay there for 23 years.

For many years after the fall of fascism, Italians turned their backs on their recent history. The fascist party was banned, the history curriculum in Italian schools even stopped at World War I. But gradually in the 21st Century old taboos are being broken.

The dress code for the celebration is rigorously black. The chants nostalgic, a medley of Fascist truisms peppered with clipped bursts of “Duce, Duce, Duce” will be hushed when the parade enters the cemetery in this central Italian town this week to arrive at its mecca: the tomb of the former Fascist dictator.

It’s always thus in Predappio, three times a year, a strange and scary group of odd fellows gather – the older black-suited Mercedes owners, the young tattooed skinheads, military-styled (also dressed in black) middle-agers, who unload black SUVs of pretty Stepford wives and two to four children, all coming to commemorate the day of Mussolini’s birth (on July 29, 1883, in a house not far from the cemetery), his death (at the hands of partisans on April, 28, 1945) or the March on Rome, which brought Mussolini’s party to power in Italy in October 1922. This year, on the 90th anniversary, the crowds are sure to be bigger and more strident in these time of economic turmoil when the trains do not run on time.

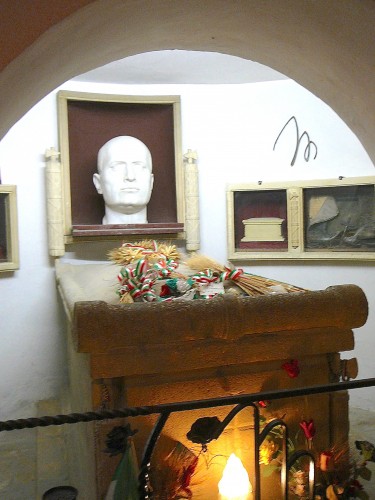

Mussolini’s tomb gets between 80,000 and 100,000 visitors a year, with peaks during the three commemorations.

After Mussolini’s corpse was hung upside down on meat hooks on April 29, 1945, in Piazzale Loreto in Milan, where citizens vented their fury at their former leader, he was buried in an unmarked grave in a nearby cemetery. A year later, neo-Fascist loyalists dug up his body and hid it in box in a convent in Lombardy until 1957, when the remains were returned to Mussolini’s widow, who buried them in the family crypt in Predappio. Supposedly, the brain took a separate path, but was eventually reunited with the corpse.

Such veneration weighed on Italy’s leaders in 1945. After Mussolini was killed, a decision was made to obscure his grave site, much the way military officials in the Transitional National Council of Libya chose to bury Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi in a secret location last month and American commandos buried Osama bin Laden at sea in May, to avoid creating a shrine for their supporters.

In fact, Italian authorities’ efforts to hide the burial site backfired on them, as its location rapidly became a matter of intense interest. “The vitality of Mussolini’s afterworld life was great as long as the mausoleum didn’t exist. A corpse that is nowhere is everywhere,” said Sergio Luzzatto, a historian at the University of Turin who wrote The Body of Il Duce about the corpse’s travels. The popular documentary Il Corpo del Duce was inspired by the book.

“Italians lived the absence of the body as a presence, so continuing the love story between Italians and their leader, which was very carnal in many ways,” Luzzatto wrote. That story ended when the body was returned to the family and “it became fixed and sepulchral,” primarily in the guest books at the tomb, where visitors can sign and leave comments. New commemorative, adoring metal plaques, dated 2011 and 2012, keep getting attached to the walls of the underground tomb where Benito is not alone – he is surrounded by the long past and recently deceased Mussolini family members.

Still this October other admirers will come to glorify an epoch in which they believe that Italy, in contrast to today, counted for something in the world. Some today think that Italy needs a distinct change – that it is the laughingstock of Europe, especially after the Berlusconi bunga-bunga years.

A museum of Duce memorabilia opened in 2001, curated by Domenico Morosini, a successful Lombardy businessman, in what was once a Mussolini summer home. The registers are shelved under a beam inscribed with a Mussolini citation: “It is not impossible to govern Italians, merely useless.” The museum gets between 2,000 and 3,000 people a year.

On Predappio’s main street, bordered by a jarring number of gargantuan Fascist-designed buildings, on a steaming hot day in August we toured a handful of shops doing brisk business in Fascist memorabilia, selling everything from truncheons to bronze busts of the long-dead leader to Mussolini calendars and authentic German helmets, circa 1945. Ever felt a cold chill climb the back of your neck on hot summer day?

This is just the kind of tourism that Predappio’s center-left mayor, Giorgio Frassineti, would rather avoid. “We refuse a vision of Predappio of the few, of the people who attend the commemorations, but also of those from the extreme left who want to cancel its history,” Frassineti told a New York Times reporter, apparently straddling the divide that splits this tiny haunted community.