“Pleasant manners,” writes Giovanni Della Casa, “are those which delight or at least do not annoy any of the senses, the desires, or the imagination of those with whom we live.”

In modern times when we are reminded that President Lyndon Johnson would hold meetings while sitting on the toilet; or there is a kerfuffle throughout the Twittersphere when Mayor de Blasio (correctly according to Italian Food Rules) ate pizza with a knife and fork; or tourists in Florence insist on greeting strangers with “Ciao!”; or foreign students think flip-flops and cut-off shorts are proper attire when touring a church, it is comforting to know that at least the Italians have Life Rules that govern almost every aspect of their daily existence. These rules were set almost five hundred years ago.

“Since it is the case that you are now just beginning that journey that I have for the most part as you see completed, that is, the one through mortal life, and loving you so very much as I do, I have proposed to myself—as one who has been many places—to show you those places in life where, walking through them, I fear you could easily either fall or take the wrong direction.”

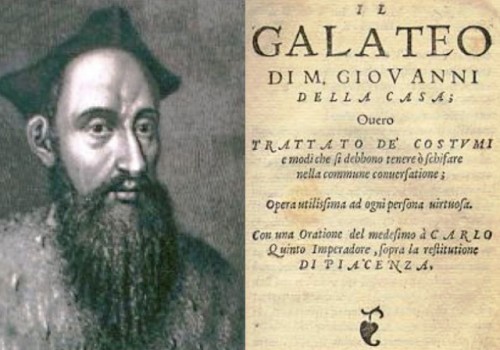

So begins Galateo, Trattato de’ Costumi (Galateo: Treatise on the Rules of Polite Behavior) a short manuscript on good manners, written by the retired, but worldly (he was known to compose racy poetry), archbishop and diplomat Giovanni Della Casa (1503-1556). First published in 1558, two years after the author’s death, it sets forth the rules on how to comport oneself in polite society.

Della Casa was born in Borgo San Lorenzo, a small town north of Florence, to a noble Tornabuoni mother and a highly educated father. He lived in Florence and Rome at the same time as Michelangelo. He attended university in Bologna and after deciding on an ecclesiastical career, he rose quickly to the position of Archbishop of Benevento, a small city northeast of Naples. His lasting legacy, however, is Il Galateo.

Purportedly for the benefit of his nephew, Annibale Rucellai, a young Florentine with an important lineage and a promising future, the treatise, in the voice of a cranky yet genial old uncle, offers the distillation of what had been learned over a lifetime of study of Greek and Roman humanistic texts and public service as diplomat and papal nuncio. (Archbishop Della Casa was once charged with setting up the inquisition in Venice to root out heretics.)

The University of Chicago Press has recently published a new edition, translated by M.F. Rusnak. As Rusnak discusses in the long introduction to Galateo: Or, The Rules of Polite Behavior, far from being a book on table manners, the original Galateo was a “conduct manual, a viable tourist guide to acting Italian in Italy, and a learned analysis of literary language.”

As relevant today as it was in Renaissance Italy, Galateo deals with subjects as varied as dress codes, charming conversation and off-color jokes, eating habits and hairstyles, and includes citations to the works of Dante and Boccaccio. Less a treatise promoting courtly values or a manual of savoir faire, it is rather a meditation on conformity and the law, on perfection and rules, but also an exasperated reaction to the diverse ways in which people make fools of themselves in everyday social situations.

As such, it holds a distinguished place among Italy’s rich history of etiquette books. These range from Andreas Capellanus’s Art of Courtly Love, which describes how a medieval knight should behave to win the favor of his lady; to Baldassare Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier, which recommends sprezzatura, the Renaissance equivalent of being nonchalant, and Machiavelli’s The Prince, devoted to realpolitik and therefore, stressing effective, rather than genial, behavior. In its time, Galateo circulated as widely as Machiavelli’s Prince and Castiglione’s Courtier.

Mirroring what Machiavelli did for promoting political behavior, and what Castiglione did for behavior at a noble court, Della Casa described the refined every-man caught in a world in which embarrassment and vulgarity prevailed. Galateo was written at a time when the medieval openness about bodily functions was being discouraged. Renaissance etiquette writers were all begging their readers to stop spitting and touching themselves in public.

Della Casa’s explanation for his rules of dress, table manners, gestures and speech is the need to avoid offending others. That is the basic bargain required to live in peaceful communities. Naturally, it never happens without a struggle. Not all Europeans agreed with Della Casa.

At the end of the 16th century, English readers assumed that Thomas Coryate, one of the earliest travel writers, was joking when he reported that Italians did not attack their food with hands and hunting knives as did normal people, even normal royalty. Those prissy Italians wielding forks arrived at the royal court in France in 1533 with the Italian Catherine de’ Medici when the pope arranged for her to marry the future King Henry II. A century later, Louis XIV was supposedly so annoyed to see a court lady use one that he had hair put in her soup.

In Richard II, Shakespeare, writing about forty years after Galateo was published, has the Duke of York complain to the dying John of Gaunt about “Report of fashions in proud Italy, / Whose manners still our tardy apish nation / Limps after in base imitation.” The French and the English disparaged Italian etiquette, only to lay claim in succeeding centuries to being the cultures of refinement, civility and propriety.

Galateo is divided into thirty chapters based around questions of etiquette. As with any modern manners book, it offers advice on proper dinner-table conversation and behavior. Have we not all been repulsed by people who, “oblivious as pigs with their snouts in the swill, never raise their faces nor their eyes, much less their hands, from the food? And they gulp down their grub with both their cheeks puffed out as if they were playing the trumpet or blowing on a fire, not eating but gobbling. Those who grease up their hands and arms to the elbows or dirty their napkins such that washcloths in the bathroom are neater.”

Throughout, Della Casa urges a reasonable conformity to the customs of the country in which one lives. (He would have encouraged Mayor de Blasio to eat pizza with his hands in NYC, but not in Florence.) Clothes, Galateo suggests, should fit well rather than be loud and trendy. He urged his nephew to follow the refined conservative fashions in Florence, but when in Naples to wear the more elaborate costumes popular there. “First of all, one must consider the country where one lives, for every custom is not good in every place. Perhaps what is customary for Neapolitans, whose city is rich in men of great lineage and barons of great prestige, would not do, for example, for the people of Lucca or Florentines who are for the most part merchants and simple gentlemen and have among them neither princes, nor counts, nor barons.”

He recommended that people speak clearly and plainly, after having “first formed in your mind what you have to say.” He argued for civility but warned against sycophancy: “Flatterers overtly show that they consider the man they are praising to be vain and arrogant, as well as so stupid, obtuse, and so beef-witted that it is easy to lure and entrap him.”

Della Casa’s message is: Don’t be disgusting. Pretty much everything that comes out of a bodily orifice met his definition of disgusting — so much so that the mere sight of someone washing his hands would upset people, as their minds would leap to the function that had necessitated that cleansing.

The counsel itself remains timeless: “Most of us hate unpleasant and bothersome people as much as evil ones, maybe even more.” In modern times, the object of Della Casa’s disparaging comments would be the woman on the bus putting on her makeup in a cloud of perfume, someone on the park bench clipping his fingernails, the teenager who insists on tapping his feet to the music leaking out of his earbuds one seat over in a plane, and those who chat or conduct business on their cell phones in a restaurant.

“You do not want, when you blow your nose, to then open the hanky and gaze at your snot as if pearls or rubies might have descended from your brains. This is a nauseating habit not likely to make anyone love you, but rather, if someone loved you, he or she would fall out of love right there,” wrote Della Casa to his nephew.

He was also irritated by people who interrupt constantly (they “surely make the other person eager to punch or smack them”), and people who describe their dreams in excruciating detail: “One should not annoy others with such stuff as dreams, especially since most dreams are by and large idiotic.”

“To offer your advice without being asked is nothing else but a way of saying that you are wiser than those you are giving advice to, and even a reproof for their ignorance and lack of knowledge.”

Americans would be surprised at Galateo’s advice on how to behave at a dinner party: “You must not do anything to proclaim how greatly you are enjoying the food and wine, for this habit is for tavern keepers.” And “[i]t is a barbarous habit to challenge someone to a drinking bout. This is not one of our Italian customs and so we give it a foreign name, that is, far brindisi.” [The Italian fare brindisi or brindare for “to toast” comes from German ich bring dir’s, “I bring yours.”]

Manners matter. As Della Casa writes, the annoyances of everyday life only seem trivial or of small moment. “Even light blows, if they are many, can kill.” In the end, regard for the feelings of others lies at the heart of any rational society. In Italy, an ill-bred bore is described as “one who has not read Il Galateo.” (Or acquired the latest smart phone app: Galateo a Tavola. )

To read Il Galateo is to have “a viable travel guide to acting Italian in Italy.” To follow its lessons is a big step toward being Italian.