Acquacotta (literally “cooked water”) is the Tuscan version of the classic tale of Stone Soup. It a simple traditional dish – in its most basic form made of water, bread and onions – originating in the Tuscan coastal region known as Maremma (often referred to as Acquacotta della Maremma). It was originally a peasant food, derived from an ancient Etruscan dish, the recipe of people who lived in the Tuscan forest working as carbonari (charcoal burners), as well as butteri (cowboys), fishermen, indentured farmers and shepherds in the Maremma region.

One purpose of Acquacotta is to make stale, hardened Tuscan bread edible. People that worked away from home for significant periods of time, such as woodcutters, fishermen and shepherds, would bring bread and other foods (such as lard, pancetta and salt cod) with them to eat over many days. Acquacotta was prepared and used to marinate the stale bread, thus softening it. The home cook, not wanting leftover bread to go to waste, would do the same. (Other peasant soup recipes, like Ribollita and Pappa al Pomodoro, alternatives to Acquacotta, were also thickened (bulked up) with stale Tuscan bread.) Those working in the forest and fields would add edible wild greens. A fisherman might cook a small fish in the broth. At home, a potato, garlic and a carrot would be added.

As noted, historically, Acquacotta’s primary ingredients were water, stale bread, onion, tomato and olive oil, along with various vegetables and leftover foods that may have been available. In the early 1800s, some preparations used agresto, a juice derived from half-ripened grapes, in place of the tomato, which was not a common food in Italy prior to the latter decades of the nineteenth century.

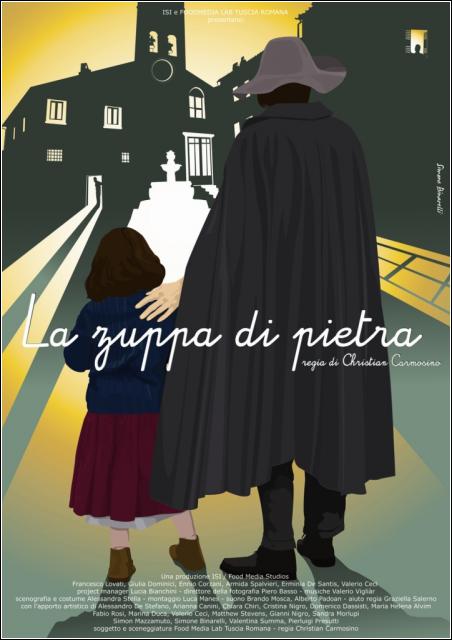

In searching for the history of the folk tales behind Acquacotta, I found a short movie “La Zuppa di Pietra“ (Stone Soup) by Christian Carmosino, which won the First Prize at the 2008 Academia Barilla Short Films Festival. The subtitled version can be found on YouTube.

(The town where the film was made is the jewel of Civita di Bagnoregio in northern Lazio near the Maremma. The population is about 12 in the winter and over 100 in the summer. It is a favorite of visiting Americans.)

In the short film, director Carmosino tells a story of a small village in rural Italy, where a traveling stranger convinces a town of suspicious residents to give him a pot of water in which he will make a delicious soup with his “magic” stone. The stranger then “tricks” various villagers to add something to the soup. It becomes a metaphor for the pleasure of a communal effort of creating a rich meal by sharing ingredients, to be eaten together around a shared table.

I found two Italian tales of Acquacotta (as opposed to Stone Soup):

One tells of a poor young girl, whose mother died when she was young. She has five elder brothers and a father. Due to her youth and their poverty, she was not able to make proper meals for her family. She decided to help her family by working for an old woman who lived in the neighborhood. She received just three eggs a day, a small portion of cheese and some bread, which were not enough to feed those hungry brothers. So instead of cooking the meager ingredients separately, the young girl decided to make a soup containing the eggs, cheese and bread, adding greens from the forest and the meadow. The simple nutritious soup became the family staple.

The other goes like this: There once was a boy called Ultimo (literally “Last One”), who was very poor and had many brothers. One summer evening, tired and hungry, he sat next to a fire in the farmyard where he worked as a laborer, thinking about what he could eat. In his pocket there was an onion. To a pot, sitting beside the fire, he added a little water, cut up the onion and cooked it. He added more water. Then he went to the edge of the meadow and discovered some wild chicory to add to the pot. He went in the hen house and took a bit of the dry stale bread left for the chickens to eat. He added the bread to the pot. His brothers called him from afar: “Ultimo! Ultimo, what are you doing?” “Nothing of importance,” he replied. “I’m just cooking water. I’m making Acquacotta.” Next time, he thought, I’ll add an egg. The farmer’s wife will never miss it. (Told, in part, by Erika of Cuoche In Vacanza (Cooks On Holiday).)

Contrary to its origins as a peasant dish, made simply of water and a few flavors, Acquacotta is now usually a very hardy soup. Contemporary preparations may use stale, fresh, or toasted bread, and can include additional ingredients such as vegetable broth, eggs, cheeses such as Parmigiano-Reggiano and Pecorino Toscano, celery, garlic, basil, beans such as cannellini beans, cabbage, kale, lemon juice, salt, pepper, potatoes and others.

Some versions may use edible mushrooms such as porcini, and leaf vegetables (arugula, kale, and broccoli leaves) and wild greens such as calamint, wild chicory, stinging nettles, dandelions, sow thistle, wild beet, wild fennel, and wild asparagus. As the greens boil down, they contribute to the broth’s flavor.

Acquacotta is distinguishable from other Tuscan soups due to its use of a poached egg (cracked right onto the simmering soup itself to poach) and stale bread added at the end of (and not during) its preparation.

One of my favorite food bloggers (and Italian cookbook author) Emiko Davies has posted a piece on Acquacotta with gorgeous photographs and a delicious modern recipe.

Giulia Scarpaleggia, food writer, photographer and Tuscan cooking instructor, provides another recipe for Acquacotta with the Italian version of the tale of Zuppa di Pietra, accompanied by beautiful photographs.