Hidden away on the top of the Palazzo Vecchio is the tapestry restoration workshop of the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, the agency that oversees all manner of restoration for Florentine museums and the artistic contents of public buildings.

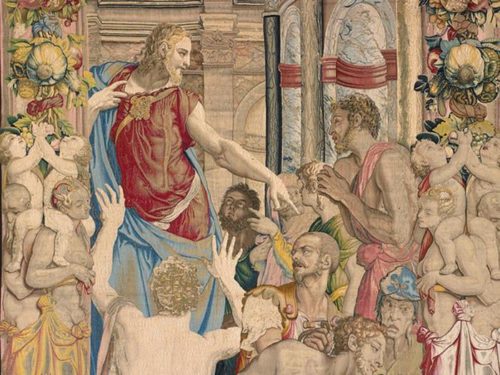

In 1985, the tapestry workshop was charged with restoration of a series of exquisite Renaissance tapestries commissioned by Cosimo de Medici in the 16th century, which were brought together for the first time in 150 years in a 2015 exhibition entitled, Prince of Dreams: The Medici’s Joseph Tapestries by Pontormo and Bronzino.

In 1545, Cosimo I, the Grand Duke of Tuscany, commissioned twenty arazzi (tapestries) telling the Old Testament story (Genesis, 37-50) of Giuseppe Ebreo, or Joseph the Jew. The twenty tapestries, stretching a collective 260 feet, adorned the walls of the Sala dei Duecento (Hall of the Two-Hundred) of the Palazzo Vecchio, for over 300 years.

In 1882, ten of them were taken to Rome to be exhibited in the Quirinal Palace, the home of the Italian Savoy kings, now the official residence of the President of the Italian Republic, where they remained until the 2015 exhibition.

Why the story of Joseph? The tapestries are masterpieces of allegory, explained exhibition curator Louis Godart, whose study found in Cosimo I de’ Medici, a man who felt he had a lot in common with Joseph.

Cosimo was from the “cadet” branch of the Medici family, one that lived outside Florence. He was almost unknown in the city until he came to power in 1537, following the assassination of his cousin, Duke Alessandro de’ Medici.

After establishing his rule, Cosimo sought to affirm his family’s political, economic and cultural primacy in Florence and in Tuscany. He sought important foreign alliances. He married Eleonora of Toledo, the daughter of Don Pedro Álvarez de Toledo, the Spanish viceroy of Naples. He wanted to raise his profile to the level of European royalty like Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain. Commissioning important works of art demonstrated both culture and wealth.

Louis Godart surmises that the story of Joseph is one in which Cosimo saw many parallels to his own life. For example, Cosimo felt he and his family had been “abandoned” by Florence and its citizens, much as Joseph had been sold off and abandoned by his brothers. Cosimo came to power at 17, the same age as Joseph when he is first mentioned in the Bible. Cosimo used skill to acquire power, much as Joseph became powerful by becoming an important and trusted adviser to the Egyptian pharaoh. Cosimo also, in time, forgave many of his enemies among the Florentine nobility, in the same manner as Joseph forgave his brothers.

In the 15th and 16th centuries tapestries were a common feature in European royal courts and the palaces of wealthy nobles. Cosimo sought out two of the best-known Flemish tapestry masters of his time, Jan Rost and Nicolas Karcher. They had already worked in Italy for the courts of the Gonzaga family of Mantua and the Este Dukes of Ferrara. The preparatory drawings were entrusted to Florentine painters Agnolo Bronzino, Jacopo Pontormo and Francesco Salviati. The tapestries, woven with the finest silk and gold thread, were hung in the Sala dei Duecento, the seat of the Tuscan ducal government, in 1545.

There are some secrets in the tapestries. Woven into the top border of many of the wall hangings there is a ram, Cosimo’s ascendant zodiac sign, as well as a symbol of spring and new birth, an allegorical message for Florence under Cosimo’s rule. Also, in a little visual pun, Jan Rost, who soon after his arrival in Florence was nicknamed l’arrosto (the roast), signed the works with a meat skewer instead of with his name.

The final result of a decades-long restoration process, started in 1985, and carried out by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure in Florence and the Laboratorio Arazzi del Quirinale in Rome, was completed in 2014. The lengthy and complicated process had to be carried out by artisans at least as skilled as the original tapestries’ makers. Godart observed, “We have the best restoration schools in the world here. Thanks to our great know-how, we can protect our patrimony and teach others.” Italian experts have been called upon by UNESCO to intervene in areas where there are great cultural treasures at risk of war, natural disasters and wear and tear, but where the local skills to protect them are lacking.

The location of the tapestry workshop plays a fictional role in the second Caterina Falcone mystery – Secret of La Specola – written by Ann Reavis. It is available at Amazon.com, Amazon.com (Kindle), Amazon.co.uk, and Amazon.it .