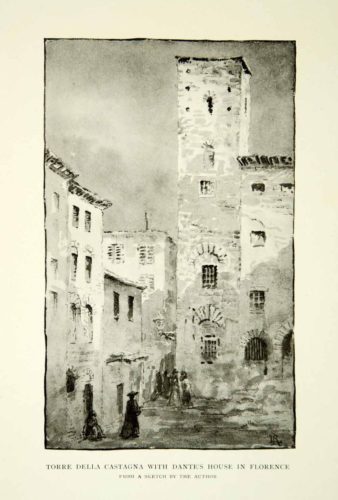

In any discussion of the hundreds of hidden towers in Florence, I always want to talk about my favorite tower, Torre della Castagna. It’s my favorite because over the centuries it is the one that hasn’t been changed to hide the original purpose of a tower: to defend those inside.

Towers of Defense: General Information

All of the other towers in the city have been altered to add windows and doors, but back when the towers were built Florence was a lawless town, controlled by families and clans that got their way by force.

A tower was built to protect a family, clan or political body and at different moments in time the now-named Torre della Castagna performed all of these functions.

I can’t find the exact date of its construction, but it must have been sometime between 900AD and 1000AD. It was first known as Torre Baccadiferrro and protected the Baccadiferro family. It was probably much taller than its present 90 feet (about 29 meters).

To look at it now (in Piazza San Martino, on the corner of Via Dante Alighieri), it is easy to imagine how dark and cold it was inside. Of course, there were no windows – to prevent burning arrows and other projectiles from entering. Light and air got in through small square holes (now cemented closed to prevent pigeons from entering). These holes were probably covered with tapestries in the winter and left open in the summer. There are no other openings on the north side of the tower.

On the west side of the square tower, the observant tourist will notice what look like three tall windows high on the wall over the front, and only, door to the tower. The very observant tourist will also see the protruding “stones” at the bottom of each of these “windows” and guess correctly that the windows are doors and that the stones are the ends of oak beams, now cut short, but once hooked this tower to another.

Imagine what it was like to live in a tower. It is tall and narrow and there is little space on each floor. Stairs climbed up one wall of each room. There was no privacy. It was dark, except for the light of lamps and candles. The kitchen and servants’ quarters were probably at the top so that if the kitchen burned up the rest of the tower wouldn’t go with it.

Back to the oak beams. To expand the Baccadiferro family’s space this tower would be attached high in the air to other towers – those of family and friends. In times of relative peace, the doors would be open, a layer of planks would be laid along the beams, and people could walk from tower to tower. (Not only was this a safety measure, but imagine the state of the Florentine dirt streets in a time of no sewer or garbage collection.)

History of Torre della Castagna

Sometime around 1038, the Torre Baccadiferro was given by the Holy Roman Emperor Corrado II to the Benedictine monks of the adjacent Badia Fiorentina in order to help with the monastery’s defenses.

In 1282 the tower became the meeting place of the Priori delle Arti of Florence. The Priori delle Arti was the governing body of the Florentine Republic. Its members came from all of the major guilds (Le Arti), such as those of the woolmakers and merchants, the bankers, the magistrates and notaries, and the silk weavers.

The Priors were elected for two-month terms, during which time they were not allowed to leave the tower unless in the company of another member, ensuring that all contact with outsiders was monitored to reduce the risk of threats or bribery. A quote from Dino Compagni’s Chronicles adorns the north wall of the tower: they then took the decision “to shut themselves away within the Castagna Tower in order to put an end to the threats fom the powerful.”

During this “interesting” election cycle in the U.S., it is appropriate to note that the word “ballot” comes in to common usage because of the Priors. They use a voting system similar to the modern-day ballot, but instead of slipping pieces of paper in a box, the Priori delle Arti used chestnuts and cloth bags.

Chestnuts were placed in bags of fabric that indicated the voting preference of each member. Although the chestnuts were later replaced by balls of wax, metal or wood of different colors, the original ballots inspired the name of the tower, Torre della Castagna (Tower of the Chestnut). In Florentine dialect, boiled chestnuts are known as ballotte. It is short step to the English “ballot.” (The Venetians like to claim credit with their word ballota, meaning a small ball.)

Torre della Castagna Today

When Florence became a free city in 13th century and a republic was founded, all towers were cropped to signify that the age of clans and civil wars was over and to give precedence to the Duomo and the Palazzo Vecchio. Florentine historian Giovanni Villani (1280-1348) wrote in his history of Florence, Nuova Cronica, that in 1251 the city government decided “all towers of Florence – and there were in big number with a height of 70 meters – to be cropped down to 29 meters or even less; the stones from the cropped towers were used to build houses in Oltrarno.” It was probably in preparation for the habitation (and name change) of the tower by the Priori delle Arti that it was shortened to 29 meters.

Visitors to Florence can explore inside the Tower of the Chestnut on Thursday afternoons because the bottom three floors of the tower are now the Garibaldi Museum (open from 4pm to 6pm).

The museum is devoted to Giuseppe Garibaldi and the veterans of the movement for the unification of Italy over 150 years ago. Flags, clothes, photos, portraits, furniture, guns and so much more from Garibaldi’s Redshirts can be found in this quirky exhibit.

I am also a fan of all things Garibaldi. And I set my short story Cats of Florence in the museum and the tower.

Of course those who love towers and could care less about Garibaldi, get a chance by visiting the museum to imagine what living inside a medieval Florentine tower was like. Climb the stairs, imagine how the rooms would be furnished, think about what living without privacy would be like, and how hard it would be to carry everything up and down the stairs of a 120 foot tower, the work of servants for medieval nobility.