Last month I took the MuseoBus through Galileo Land. First stop – the Galileo Museum.

Last year, Florence’s History of Science Museum finally reopened with a new name – Museo Galileo. The exhibits that were once a bit musty and dusty are now beautifully presented – well lit, dramatic, modern and packed full with beautifully made instruments for observing and demonstrating the world around us. It’s all polished brass, finely turned wood and carefully blown glass.

We were there to appreciate the science of Galileo and so concentrated on his telescopes with which he found the moons of Jupiter and the globes and maps of the ever-changing views of the world. (Later, we came back to see the historical medical science instruments, 18th century chemistry equipment, and more, located on the Galileo Museum’s top floor.)

One of the most impressive exhibits, a huge armillary sphere (1593), ordered for Grand Duke Ferdinando I, is a great example of art and science working together. It stands over 11 feet tall, made of gold and cypress wood, showing the Ptolemaic orbits of all of the planets and the sun around the earth – everything Galileo argued against – and it still rotates, having been restored for the opening of the new museum.

And then there is the finger – the middle finger of Galileo’s right hand, sits in a glass case held perpetually upright. It’s not pointing anywhere in particular, but it’s hard not to smile at the potential for symbolism given history has proved Galileo right in spite of his being forced to recant. It was alone until 2009 when it was joined by another finger, a thumb and a molar. (The stories of their very existence, as well as their subsequent rediscovery, are too long to recount here so go read the amusing version from the New York Times.)

Our next stop on the MuseoBus was Villa il Gioiello (“The Jewel”) Galileo’s last home in Arcetri, a little town just a mile south of Florence, up in the hills. (A popular restaurant with tourists, Omero, a 15 euro cab ride from central Florence, is right across the street from Villa il Gioiello, but most diners don’t realize that they are walking in the footsteps of Galileo.)

Sentenced to house arrest by the Inquisition in Rome for defending the revolutionary sun-centered Copernican universe against the traditional earth-centered Ptolemaic world-view, Galileo returned to his Arcetri house in 1633, and stayed there until he died in 1642. It is also known now as Villa Galileo (not to be confused with the other homes of Galileo found in Florence, which are in Costa San Giorgio, as well as a villa in Bellosguardo).

The name Gioiello was given due to its favorable position in the hills of Arcetri, near the Torre del Gallo. It was an elegant home, surrounded by many acres of farmland with a separate house for workers. It is recorded in the cadastre of 1427 to have been owned by Tommaso di Cristofano Masi and his brothers, who later passed it on to the Calderini family in 1525, where it is first mentioned as “The Jewel”. The villa and its estate suffered damages during the siege of Florence in the years 1529 and 1530, whilst the entire area of Arcetri and Pian dei Giullari were occupied by Spanish Imperial troops. Calderini sold it shortly thereafter to the Cavalcanti family, who rebuilt the home with its original simple lines, preserving its elegant look to the present day.

This residence, rented by Galileo, was near the monastery where his daughter, Sister Maria Celeste (born Virginia) was a nun. There are 124 remaining letters from Celeste to Galileo (the replies of the scientist were probably destroyed), which were found after his death and are now at the State Archive of Florence. A popular book, Galileo’s Daughter, recounts that correspondence. Sister Maria Celeste died in 1634.

Despite becoming blind in 1638, Galileo continued to write some of his most significant works – Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Relating to Two New Sciences (Discorsi e Dimostrazioni Matematiche, intorno a due nuove scienze) – in which he presented his theories on the strength and resistance of materials and on motion.

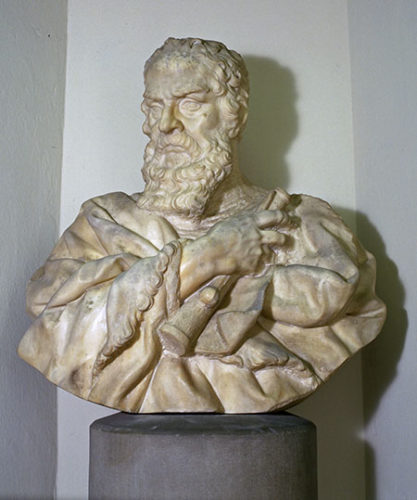

Shortly after Galileo moved to Arcetri, he received visits from Grand Duke Ferdinando II de’ Medici as well as the painter, who painted his portrait. Other guests were the Ambassador of the Netherlands (Galileo had printed many of his books in Leiden) and the English poet John Milton, who was so impressed that references to Galileo’s telescope made an appearance in Paradise Lost.

The MuseoBus tours are a fantastic way to get to less central museums and other historic locations. Each itinerary starts at a museum in the historic center and then goes out to a destination too far to walk to. The tours themselves are in Italian, directed by very knowledgeable guides, but even if you don’t understand everything said, the bus service makes it all worthwhile.