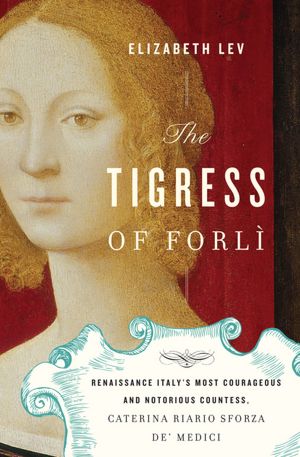

How do you create the perfect Renaissance superhero? Art historian, Elizabeth Lev, narrates the story in her fascinating book, The Tigress of Forlì. The story starts with a baby girl, Caterina Sforza, the illegitimate child of dissolute, but noble Milanese father and a drop-dead gorgeous mother. She is tutored in the classics, learns how to ride a horse and hunt, and masters the management skills of a great household. Then her father arranges for an engagement at age ten (consummated with the fiancée, aged 30) and marriage at age thirteen (blessed by the Pope). She gives birth of her first child at fifteen.

As her greedy self-serving husband’s health deteriorated, Caterina keeps providing heirs (six), but also takes over the governance of their dominions (Imola and Forlì). The cowardly husband is assassinated and all seems to be lost, but our pregnant superhero escapes her captors, takes up arms and captures the castle. All this happens before she turns thirty.

Then there is a steamy affair with a stable boy, a murder, and a bloody revenge. Machiavelli turns to negotiate peace, she marries a Medici, gives birth to the father of a future Tuscan Grand Duke, is widowed again, and finally loses her castle to Cesare Borgia. This, of course, is not the end of the story. She’s only 36 when Borgia drags her off to prison in Rome. (Spoiler alert: She lives to play with her grandchildren in Florence.)

Elizabeth Lev doesn’t fictionalize Caterina Riario Sforza de’Medici’s life. She doesn’t need to because this is a true case of truth being more amazing than fiction. No, Elizabeth only had to spend years in the archives of Bologna, Florence and Rome, gathering the facts from the dusty pages of history and the spinning them out in a breathtaking narrative of the tale of a true superhero.

Elizabeth, whose formidable resume takes pages to recount, agreed to answer a few questions about her life and The Tigress of Forlì.

I was transported reading your book The Tigress of Forlì, not only to the 15th century Italian city-states, but also to the Italy of today with its convoluted politics, family dynasties and love of gossip. Am I wrong, or has nothing changed in 500 years?

This is what makes history so fun. Human beings, the human condition, means that every age experiences desire for power, pleasure and possessions; but how it plays out against different backdrops and settings has an infinite variety. But amid the schemers and the scandalmongers, a few exceptional people stand out for forging their way in a complicated world and leaving a distinct mark. Caterina Sforza makes a wonderful guide to this era, as her unique viewpoint, enhanced by very human susceptibilities, shows us the Renaissance like we’ve never seen it.

What path did you take from life in the United States to ultimately living in Rome?

I always wanted to live in Europe, even as a kid. Whether it was Ian Fleming’s Bond novels or the Greek myths or the romances of Jane Austen, it seemed to me that all the cool stuff was always happening in stately drawing rooms or under marble porticos or driving along through picturesque European villages. It didn’t take long for me to discover the pictures that made the world even more brilliant: a Dutch still life or Florentine fresco. From the University of Chicago, I was thrilled to be able to study art history abroad for a year at the University of Bologna, and when I finished my degree, I came back to Bologna as a graduate student. My thesis director suggested I write on a Roman subject, and the rest is history.

It seems to me that you were working on a thesis when you were writing The Tigress of Forlì. First, how did you find the time and second, what was the subject of your thesis?

I first ran into Caterina when writing my thesis on the National Church of the Bolognese in Rome (Santi Giovanni e Petronio dei Bolognesi) while tucked away in Imola, where this glamorous countess had lived far away from the city lights for many years. I sympathized with her story—city girl transplanted to the country life—but didn’t actually start the book on her until many years later. At the time I was writing The Tigress of Forlì, I was the single mother of three kids, two teens and a toddler, with two teaching jobs, a regular news column and a full-time schedule of tours. Fortunately, getting up early is easier when aided by fine espresso and the hours spent with Caterina were like spending time with a dear friend.

Why did you decide to write about Caterina Riaro Sforza de’ Medici?

What a woman! What a story! Although victimized, she never made herself a victim, and always got up after any kind of fall. She lived in thrilling times: Machiavelli, Leonardo da Vinci, Lorenzo the Magnificent, Pope Alexander Borgia, and she played a significant role wherever she went. Caterina was no wallflower. She left her mark, whether with her beauty, her courage or her cannons. She was an amazing challenge to understand. Not all she did was pretty, and to get inside the head and the world of a woman who made such surprising decisions took a lot work, but was so wonderfully worth it!

In reading the book, it seems at times that you get so under her skin that you begin to identify with her. Was this a plus, or did you have to make sure you weren’t projecting yourself on her?

There were many things in Caterina’s life that I identified with: being a single mother, and trying to figure out how to keep a family afloat in difficult circumstances among others. Indeed, I believe I brought a unique perspective to certain aspects of her story because I evaluated her options as a woman who had known similar situations. In some cases, where men dismissed her as power hungry or simply inept, I saw strategy. The hardest part to write was the tragedy of her wrongdoings. Caterina made terrible mistakes. In those cases, I found myself not projecting, but looking to her to see how one keeps going after a very public and humiliating fall. I must admit, there were days when I wished I was as tough as she was!

Caterina Sforza appears to be a very liberated, strong woman, once you get past the fact that she was engaged at age ten and forced to wed at age thirteen. Was she unique or were there other women who were equally agile at working the power dynamics of their time and assertive in taking the initiative?

Actually, there are many more remarkable women of the Renaissance than we recognize. Caterina grew up in a world that celebrated a 14-year-old girl named Agnes who had defied the Roman Empire, a world that named a Bolognese woman as patroness of artists, and Caterina herself was named for a 20-something woman from Siena who told the Pope “to be a man.” She was admired by Isabella D’Este—art patron extraordinaire—and knew Lucrezia Borgia (although she didn’t think much of her).

The women of the Renaissance were trained to be circumspect and modest, but they were also adept at running businesses and complicated households, and at times engaged in the battles for power that raged in their time. Very few actually found themselves in situations where the ability and will to rule came to the fore, but they were formidable when they did. Some dazzled with charm and others with ruthlessness, but Caterina had a substantial dose of both.

Caterina Sforza was an iconoclast in her own time – men rose to fight wars at her behest, wrote poetry in her name, sent snarky reports about her behavior, and debated the political wisdom of killing her off – but it is hard for me to determine how an illegitimate pawn of a noble family got on this rollercoaster to fame. Was it nurture or nature?

Caterina’s father, with all of his obvious flaws, believed in education, whether for sons and daughters, legitimate and illegitimate. As condottieri, the Sforza family also understood that ability to command and to wield weapons was their lifeline. Hunting, like sports today, also taught important life skills for that age. Take that kind of training and put it into a package of natural beauty, fashion sense honed in the glamorous Milan court, brains nourished by Greek philosophers, Latin politicians and Christian thinkers, then add a sense of self-worth given to her by family and faith, and you have the stuff of legend and song.

In a time without Facebook and Twitter, the word of Caterina Sforza’s antics seemed to spread throughout the peninsula and into France and Germany. Was this the reality or is just that in The Tigress of Forlì you are recounting the reports sent to various noble courts? Did the common man in Rome or Florence know of Caterina Sforza or was she just the concern of the highest levels of the church and the nobles of warring city-states?

Before Facebook and Twitter, the story had to be really good in order to spread. The ease of information in our age has led to an indiscriminate sense of its value. But an astounding character, like Caterina, who had impressed armies, would soon find pan-European fame, thanks in large part to the mobility of soldiers. They sang ballads of her in France, (“For a good fight call….”), and they whispered about her in Rome. Obviously, in the modern age, she would have been much more notorious, but perhaps the incessant hammering of the modern news machine would have stifled her. It is one thing to make outrageous choices with a few court ambassadors scribbling by the sidelines; it would have been another thing altogether on the ramparts of Ravaldino with news helicopters flying overhead and paparazzi hiding in the bushes.

Please describe how the research for this book was done. How many archives did you use? Were you handling original documents or had they all been copied? What was the best “ah ha” moment you experienced in the research?

The most fruitful were the archives of Milan, Forlì and Florence (where they kept accounts of everything!). It is amazing how well-informed these princes and leaders were. The Vatican archives allowed me to handle the diaries of Pope Sixtus IV, which were so intimate they made me feel like I was in the room at times. Most were copied, except for a few diaries, where the notes in the margins and a text alteration that had happened during Caterina’s lifetime were crucial parts of understanding the text.

I was struck when I read the accounts of “the retort at Ravaldino,” the most famous event of her life, at how many different versions there were of the story. As I read each account, then read the author’s other writings, then researched the author himself, I began to see how much chronicles and accounts were manipulated in that age. One tends to think that these writers were serious men with a weighty sense of their duty to posterity, but one is a gossip, one is a stalker, one is trying to forge an alliance, one is hysterically prim and so on… It is sort of like reading the Italian newspapers today—read five stories, take an average mean, and you will wind up with an approximation of what might have really happened.

What I enjoyed most about The Tigress of Forlì is that it is a researched (and footnoted) work of nonfiction that reads as smoothly as fiction. This appears to be your first book. How were you able to achieve the descriptive flow?

I have been leading tours for fifteen years and teaching sophomores at Duquesne University for twelve. If you can’t tell a story and weave your facts into vivid picture of people and events, you will find yourself with snoozing tourists and students succumbing to their hangovers. Of course, much of the credit is due to my editor at Harcourt, who had the good sense to tell me to cut out a lot of the academic sounding explanations and always encouraged me to try to find the “voice” of my characters.

This story is so colorful, so exciting, so full of adventure that it almost reads like a movie script. Have you considered making the book into a movie or television series?

As I was writing the book, I saw much of it happening in my mind. The amount of information available allowed me to imagine the sets, the extras, the scenery and of course, as I got to know the people, I would sometimes cast them in my head. It was a great help when trying to get through rough spots where the words just stayed still and dry on the page, to try to see the events taking place, the exchange between the characters, and wonder who would make a good Caterina or Cesare Borgia or Machiavelli. But sadly, Caterina remains for the moment alive in words instead of images.

There are hundreds of convoluted family relationships, fluid political alliances, arcane minutiae about everything from home life to warfare, and more. Did you have a wall full of post-it notes and string to help keep it all straight?

It was a daunting task—learning about the Salt Wars, the Riario dynasty, the fluctuating friendships—and I grew to think about my job as “making perfume.” I’ve heard it takes 60,000 roses to make 1 ounce of rose oil. In many cases to get an event or dynasty straight, it felt like 60,000 sources for one paragraph!!!! The hardest part, however, was seeing my hard-researched work wind up on the editor’s floor. In earlier drafts I meticulously outlined the conflicts and characters, only to have my editor sweep in with her red pen and cut, cut, cut. My editor was a saving grace for the book, however, because a small dab of rose oil is fragrant, but being doused with it would be stifling!

I like to tell visitors to Florence that families like the Medici operated on the “five son formula” for successful dynastic growth. One son for the family business, one for the military, one destined for politics, one entered the church, and a spare. Did Caterina Sforza ascribe to this theory? If so, why were her sons so disappointing? Again, nature or nurture?

Caterina’s children made me much more patient with mine. Her older sons were too lazy for dynasty, too dumb for politics and too cowardly for the military. The interaction between Caterina and her oldest son was so tragicomic at times; they could have had a reality show! Her youngest son was, of course, her darling and became the hero known in the peninsula as “L’Italia”, and her daughter trusted her to help raise her own children, so despite the failure with the oldest boys, Caterina eventually must have done something right.

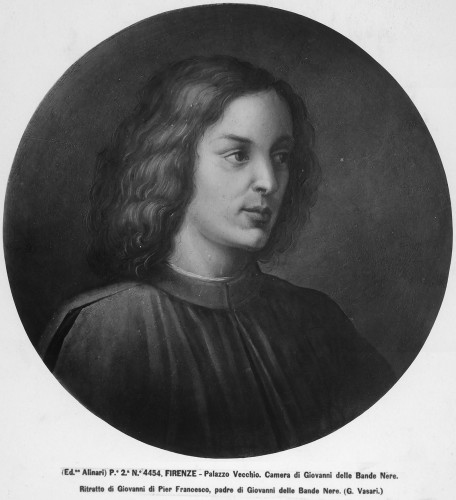

Finally, Botticelli. Did Giovanni de’ Medici, Caterina’s last husband, grow up in a home where Botticelli’s Primavera and Birth of Venus were on the walls? Did Giovanni’s father commission these paintings? And, how did you learn that Caterina is depicted in The Purification of the Lepers by Botticelli, located in the Sistine Chapel?

The earliest mention of Botticelli’s two most famous works has them in the Medici Villa Castello owned by Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici of the cadet branch and brother of Caterina’s husband. Caterina herself also lived there at the end of her life. Lorenzo is also the one who commissioned the illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy from Botticelli. I find it comforting that this warrior princess found true love with a family of great art patrons—no wonder Botticelli loved painting images of how love conquers all!

Ludwig von Pastor, in his History of the Popes made an interesting excursus into the panel paintings of the Sistine Chapel. To be honest, he identified Caterina as one of the daughters of Jethro in the Botticelli image on the opposite wall. But Pastor also pointed out that the Purification, across from the papal throne, had several unique qualities that were all family references. I knew Caterina was pregnant at the time; all sources said that Sixtus doted on her, and the viper playing around the child’s feet seemed to allude to the Sforza family symbol. It was a great moment to be able to make a new argument for her identity in that great space!

What led to your involvement in the book, Roman Pilgrimage: The Station Churches?

George Weigel has been a friend of mine for years and indeed it was he that introduced me to my agent when it came time to publish The Tigress of Forlì. George came to me when the Caterina project was over and asked me if I would like to co-write a book with him. He is an outstanding writer, with great turns of phrase and clear, powerful prose and I was honored to be part of this project. It was wonderful to be able to see these Roman churches as part of a community of worshippers and to feel the connections between the buildings we admire today and the burgeoning, vibrant Christian community of sixteen hundred years ago.

Do you plan to write another biography? If so, of whom?

I have recently published a book with Father José Granados on the Theology of the Body as expressed in the art collection of the Vatican Museums, and now I am trying to get back into more of an art history groove. I am looking to work on something involving Michelangelo and I am also looking at another project to capitalize on my specialized knowledge of the Vatican collections.

A review of The Tigress of Forlì by Elizabeth Lev can be found here.

Buy it at Amazon.com or Amazon.co.uk or Amazon.it.