“Viva Fiorenza” bellows the crowd of over two thousand, echoed by the roar of a cannon. The noble horsemen, clad in velvet, gold and leather, gallop on huge stallions into the sand-covered piazza. “Viva Fiorenza” and the cannon booms again, the sound bounces off the imposing marble facade of the Church of Santa Croce. Armored foot soldiers, alabardieri, with Florentine iron helmets and leather corsalets, armed with halberts and swords, march forward in time to the beat of twenty drummers wearing yellow and blue silk tunics, the crimson Florentine lily emblazoned on their drums.

“Viva Fiorenza” and trumpets blare, calling more than four hundred dignitaries — politicians, judges, bankers, military officers, wealthy merchants, and nobility — to parade around the square in their costumes of Renaissance finery. Even in the atomic age it is easy to step back in time for a few hours in Tuscany, especially in Florence.

“Viva Fiorenza” — the Ball Bearer, carrying a green and a blue soccer ball, one each hand, slowly begins to circle the field. Twenty-six infantry officers wearing multi-colored uniforms and feathered caps follow him. Two oxen drivers, dressed in white smocks and leather vests, lead in a young flower-festooned heifer, the coveted prize of the day.

“Viva Fiorenza” — the cry is louder as squads of men enter carrying huge flags on long poles. Each group is distinguished from the others by the color and decoration of the flags, which match their uniforms — short tunics, tights and soft leather boots. Of the sixteen flags groups, one represents the Masters of the Salt, those who provided for the tax on the consumption of salt which each citizen had to pay — their flags are white with a red covered cup; and another, the Masters of the Mint, providers of silver and gold coinage, have flags of blue sown with gold coins. To drum beat and trumpet refrain the bandierai wave, throw, dip and exchange their banners in elegant choreographed maneuvers. The cannon thunders as the flag teams retire the field.

“Forza Verdi”, thunders half of the assembled audience, those standing in the bleachers at the end of the piazza nearest the church. Into the arena, behind a richly costumed standard-bearer, stride twenty-eight men in dark green short-sleeved shirts, matching long green stockings, leather shoes, and mid-length voluminous green and purple striped pants gathered in a tight band below the knee. They line up at the end of the square near their admirers. The cannon reports again.

“Forza Azzurri”, clamor the people at the other end of the field, rising to their feet and rattling the metal stands in their zeal. Another resplendent standard-bearer leads in a squadron of men dressed similarly to the first except their shirts and stockings are blue, and their capacious pantaloons are blue and purple striped. They gather at the opposite end of piazza from the green team. The procession is complete. It is time for the Calcio Storico Fiorentino, the historical football game, to begin.

On February 17, 1530, the residents of Florence produced a similar extravaganza in Piazza Santa Croce in full view of the armies of Spain and Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, which had been laying siege to the Tuscan city for over five months. Following the pageantry, with the extreme irony that only Florentines possess, although hungry and exhausted, they thumbed their collective nose at the invaders by staging a game of football, calcio in livrea or football in livery. In modern times, that famous game is replayed every year on June 24, the feast day of Florence’s patron saint, San Giovanni, John the Baptist. It is now the grandest event and display of historical and cultural tradition in the Florentine calendar, rivaling the Palio of Siena — the yearly horse race — in pomp and rich pageantry. Like the Palio, the Calcio Storico is not only a reflection of the past, but also is a bloody, violent competition between rival neighborhoods of the city.

I saw my first game almost ten years ago and have been in the stands on at least one other occasion. I was impressed by the grand pre-game procession, rich in dignity and charm; but it was the game itself that left me flabbergasted. It’s a brutal contest played on sand by men wearing tights, bloomers and t-shirts — no pads or helmets in sight. In ’99, I sat with the victorious Reds, and the next year, with the loosing Greens.

There are four neighborhoods of Florence, each known by the major church in the area, and each represented by a team for the historical football game: Santa Croce has the Azzurri, the Blues, San Giovanni supports the Verdi, the Greens, Santo Spirito has the Bianchi, the Whites and Santa Maria Novella sponsors the Rossi, the Reds. Each June, on the two Sundays before the Festa di San Giovanni there are two play-off games to decide the finalists.

I was told that the players are volunteers in their twenties or thirties and that about ten years ago a new rule mandated that no one with a criminal record could play for a Calcio Storico team. In ’99, From the front rows most of the players looked like Michelangelo’s David on steroids — each with that classical Italian profile, but with bigger biceps and pecs. A number of the older ones, however, had flattened noses, the price of too many games.

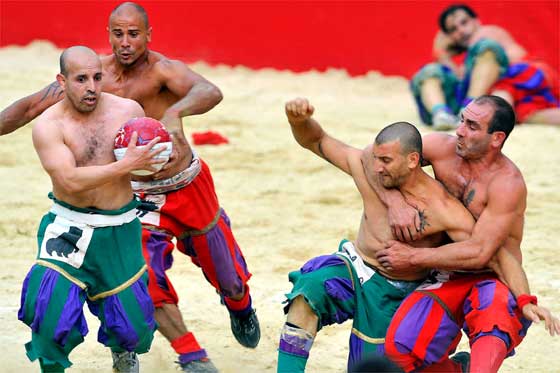

The sport is a cross between Greco-Roman wrestling, rugby and soccer. Goals are scored by pitching the round red and white leather ball over a four-foot high wooden wall that runs the full width at each end of the field. Quixotically, a tall narrow white tent with red trim and a small red flag on top is positioned in the center of each goal wall. In front, stands the captain of a team and a standard bearer with the team flag. When a team scores, the cannon is fired, the scoring team’s standard-bearer runs the length of the field waving his flag with his team running behind, cheering. The other team’s standard bearer slinks down the field and the teams change goals.

The ball is not moved on the ground — it must be too hard to kick the heavy ball through the sand — but instead, the players run with it or pass it. While half the team is moving the ball, the other half wrestles one-on-one with opposing players in some sort of defensive scheme. Sometimes when a player had been pinned for a long time one of his teammates will come along and take his place, wrestling the opposing player off the poor soul whose face is being ground into the sand. Almost all of the combatants have their shirts torn in two and ripped off their backs by the end of the game. The defensive wrestlers spill the most blood. The only player I saw carried off the field on a stretcher, however, was injured in the post-game procession when a horse kicked him.

Six referees, wearing soft velvet caps adorned with ostrich plumes and jewel-toned velvet doublets and puffy knee-length pants, observe different parts of the game; some watch the ball being moved, others watch the wrestling; they do not intercede often. A referee judge carries a sword, but I never figure out how it was used in his deliberations. He swept off his plumed hat to signal changes of side and to award goals.

There was a lot of kissing after the game, before the awarding of the heifer to the winning team and the final parade of dignitaries. First, the triumphant players kissed each other. Then, the victorious were kissed by hordes of girls wearing spandex pants, and shoes with stiletto heels. Finally, these sweaty, bloodied warriors were kissed by their mothers. In Italy, even the most ferocious of men is a mamma’s boy.

I can now see it on TV, out of the sun and out of the crowds. Two years ago, my touring clients – a family of six from Portland, Oregon – wanted to experience the game a mere ten bleachers from the field. That’s where I saw them on TV – a six- and nine-year old in baseball caps and the rest of the family, behind noble ladies and gentlemen in historical dress of the 16th century – cheering on the sweating, bloodied heroes of the day.

This year, I am hearing about the pageantry from Santa Fe. Next June, you should come to Florence and see football as it has been played for over five hundred years with Italian passion, blood, sweat, tradition and pageantry.